On the number 362 of A, in May, I introduced some of the worker-owned cooperatives operating for decades in the United States.

The main area of distribution of these cooperatives is certainly the Bay Area of San Francisco, California.

I have already spoken of the chain of bakeries Arizmendi, operating in the Bay Area, I now explore the issue with a paper on the structure of this set of 7 cooperatives that have proliferated while maintaining the independence and participation and democratic control from below each of them, while equipping of a support structure, logistical and administrative control from below, which also open up new cooperatives and having them take off. The experience of the group draws on the experience of the Mondragon cooperatives of the Basque Country in Spain, although not directly copying their structure. Arizmendi Cooperatives are viewed in the U.S. as a model to imitate reality as to broaden the cooperation in other fields and other areas of the United States.

I have already spoken of the chain of bakeries Arizmendi, operating in the Bay Area, I now explore the issue with a paper on the structure of this set of 7 cooperatives that have proliferated while maintaining the independence and participation and democratic control from below each of them, while equipping of a support structure, logistical and administrative control from below, which also open up new cooperatives and having them take off. The experience of the group draws on the experience of the Mondragon cooperatives of the Basque Country in Spain, although not directly copying their structure. Arizmendi Cooperatives are viewed in the U.S. as a model to imitate reality as to broaden the cooperation in other fields and other areas of the United States.

The second article this month concerns another cooperative experience, also of San Francisco, an experience born from the struggles of the workers union of the show in a theater. Read the article to see what it is the show ... and, please, do not be offended!

Enrico Massetti

enricomassetti@msn.com

.

The Replication of Arizmendi Bakery:

A Model of the Democratic Worker Cooperative Movement

by Joe Marraffino

Arizmendi Development and Support Cooperative

Since the mid-1990s a group of worker cooperative organizers in the San Francisco Bay Area has been developing a new model for cooperative development. Our organization, the Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives, is a network, incubator, and technical assistance provider that is owned, governed, and funded by the member workplaces it creates and serves. Our primary activity is to replicate and offer continuing support to new retail bakeries based on a proven cooperative business model.

This new model seeks to work around some barriers to the growth of the cooperative movement. One of these barriers is the tendency for cooperative development work to be done in contexts that have high rates of failure. When the Association is ready to develop a new bakery cooperative, we find a new site, draw new capitalization loans, recruit new worker-owners, and face the risks that any new enterprise faces. However, these risks are reduced by what is not new: the enterprise adapts the same business plan that existing member bakeries have used, it offers a tested product line using the same recipes, it has a similar name and co-advertises to nearby markets, it uses proven governance structures, and it shares the cost of support services with other members. It even houses some of the same sourdough starter culture. Building on these similarities, the new worker cooperative bakery will cost less, start faster, and be more resilient than an unprecedented business. This initial advantage is reinforced by a network of similar businesses offering mutual aid, and by enduring technical assistance.

Another growth barrier of the worker co-op movement this model addresses is the limited and irregular availability of funding for co-op development organizations. Development funding for the Association comes from member workplaces who contribute a percentage of their net income as membership fees. If the workplace is not profitable yet, they pay nothing for membership but still receive full technical assistance services. As workplaces mature, the income to the Association increases, and with it the funds available for development increase. The income projection for the Association curves upward: the more profitable businesses we develop, the more contributed fees are available for development. The Association has developed three businesses in a decade without any external philanthropic contributions, and is poised, now in 2009, to develop another.

As a member of this association, I'm happy to describe some of our model here, with the hope that others in the worker cooperative movement may find elements to borrow.

.

The Origins of the Arizmendi Association

In San Francisco during the 1970s a wave of small worker cooperatives self-organized, and several local organizations formed to develop and support democratic businesses. The InterCooperative, a regional network, began publishing a directory listing scores of cooperative and collective businesses. The Alternatives Center published a newsletter on cooperative activities, and sold technical guides and videos on cooperative process. The Democratic Business Association offered legal and organizational consultation. Some new cooperatives branched off from existing ones. The Cheese Board Collective, a retail artisanal cheese and bread store cooperativized in 1971, and then split the organization into two internal cooperatives when their pizzas sales grew formidably. During its history members left and opened a cooperatively-run restaurant, a juice bar, and another cheese shop. With each of these divisions, the Cheese Board lent money to the new developments, but did not hold equity in them or require any future organizational relationship to them.

Few of the small cooperative businesses had the resources to pay for technical support. By the mid-1990s only a handful of co-ops listed the 1970s directory were still operating, and few of the support organizations were active. During this period, there was renewed interest in organizing cooperatives in the Bay Area. A new regional federation, the Network of Bay Area Worker Cooperatives, began to meet informally. Women's Action to Gain Economic Security (WAGES), a nonprofit business incubator, was formed (See article on WAGES in this issue). In 1995, the Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives, a cooperative corporation, was founded. The organizers of the Arizmendi Association were three alumni of previous support organizations, and included a veteran member of the Cheese Board.

The organizers sought to overcome some of the obstacles made visible by previous worker cooperative development projects. One was the negative feedback dynamic of a fee-for-service income model: the more a cooperative needs help, the less they are likely to pay for it and get it. This influenced their strategy for membership and dues. The organizers also realized that attempting to develop an expertise in many different kinds of businesses was labor intensive and increased the chances of failure. They decided to choose a thriving worker cooperative, to become experts in that one business model, and to replicate it many times. In doing so the development and support services would get more efficient as more cooperatives were developed, not less, as they would if every business were very different. With that in mind, they recruited the help, and founding membership, of the Cheese Board Collective.

In the 1995 the organizers approached the Cheese Board with the idea of helping to create "the largest possible number of decently-compensated work opportunities in democratically operated businesses that function as part of an interdependent economic framework." With great generosity, Cheese Board Collective members offered their recipes, their organizational structure, startup funding, and use of their name in marketing. Over a decade later, when customers realize that the Arizmendi Bakeries are connected to the Cheese Board, the bakeries enjoy an immeasurable boost in value and legitimacy due to the "mother" store's reputation.

The Replication Cycle. The replication process can best be seen by looking at the structure of the whole organization.

The Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives is a cooperative corporation with two membership classes. At present there are four corporate members: the Cheese Board, and three "Arizmendi Bakery" replications of the Cheese Board model that the Association developed. These businesses are independently owned, and are members of the Association on a voluntary basis - however, the use of the name Arizmendi and the right to trade secrets, such as recipes, are restricted by contract in the event a business should want to leave the Association. Each corporate member elects two delegates to sit on the board of directors of the Association, which we call the Policy Council. The Policy Council determines the aims of the Association, the level of fees required, and the services the Association will provide to its membership. The other membership class is for an internal staff cooperative known as the Development and Support Cooperative, or the DSC. This group also sends delegates to the Policy Council.

Corporate members contribute a portion of their income to the Association, the formula for which is set as a percentage of net profit for the first several years. This is a relief to the newborn cooperative when it has no profit in the first year or two, and also an incentive for the Association to create businesses that will become profitable as soon as possible. As the business matures, the formula transitions to a percentage of sales, modeled loosely on a franchise relationship. Often this means that the cooperative pays least when it requires the most help and more when it requires less help.

Annually the Policy Council mandates and budgets for the activities of the DSC. The DSC provides bookkeeping, legal aid, new member educational workshops, facilitation and conflict resolution services, organizes cross-Association communication, and contracts with outside professionals to offer the members tax advisement and other professional services. (Because of its special role as the original business model, the Cheese Board's fees and the services they use are negligible compared to the other members.) At present, the DSC's total labor hours hover around the equivalent of one full-time worker, currently divided by four members. While there is no fee-for-services equation to the fees contributed, there is also no limit to the intensity of services a member might request. A disproportionate amount of the budget might be used to help a struggling member if needed. Barring such a crisis, the Policy Council budgets for a surplus after offering support services. This surplus is used for another of the organizations aims: job creation.

When the Association is ready to develop a new cooperative, its staff enlarges to include trainers from the existing member bakeries. These trainers work in the new store for as much as six months, in order to communicate skills and demonstrate democratic communication to the new workers. At the end of this period, the trainers withdraw to their home bakery. The Association pays both for this training and for DSC development services, such as facilitating the work of an architect and contractor, negotiating loan and lease terms, incorporating the new cooperative, recruiting members, and offering financial and organizational training. The Association also puts in place a Contract of Association defining the relationship between the new and existing cooperatives. Finally, the DSC facilitates the lending of startup capital to the new cooperative. The debt will not be incurred by the Association, but by the new, independent business.

Starting with only the Cheese Board and the DSC, the Association has replicated the business model three times in a decade. It accomplished this without the philanthropic grants; though it did receive some startup money from the Cheese Board and unsecured loans extended in good faith by individuals in the Cheese Board's community. Each development cycle has exhausted surpluses generated by member fees, and a fallow period without development activities has followed. These fallow periods will diminish as the Association develops more members.

The Organizational Structure of the Arizmendi Association and the Cycle of New Co-op Development:

- The organizational structure of the Arizmendi Association.

There are five bakeries in the Association. In addition there is an independent Development and Support Cooperative (DSC) that provides legal and business services for the bakeries and plans and organizes new startup bakeries. Each of the bakeries and the DSC elect members to the Policy Council which manages the Arizmendi Association.

- The relationship between the policy council and DSC.

The Policy Council mandates the goals and policies for the services offered by the DSC. The DSC provides legal and business services to the bakeries.

- Starting a new bakery.

The Policy Council decides to start a new bakery providing some of the start up cost and a contract of association. The DSC organizes the startup. Startup activities include such activities as choosing a location for the new stores, arranging for startup capital, and coordinating training of the startup co-op's members. Established bakeries provide trainers for the new co-op.

- The new bakery joins the Arizmendi Association and elects members to the Policy Council.

In  the future, there are different ways the Association could develop. While this structure has done well for us, it has also been a creative experiment adapted as needed. Our current strategy is to saturate the Bay Area with the one business model, as it is the most efficient use of our still-limited resources. However, the market for neighborhood bakeries is not unlimited. Before we are able to sense such a limit, the member bakeries themselves will probably choose to restrict replication, in order to protect their perceived territories. Some members envision selecting another business model to replicate. Others envision reaching a critical mass of bakeries such that we might create jobs vertically - a flour mill, for instance, or an equipment maintenance team, or even a lending institution to offer capital to new developments. In another vision the Association would replicate itself and begin to create Arizmendi Bakeries in another city ? but because the efficiency of our support services increases with our density, and because trainers for new developments have historically worked part-time in their own cooperative and part-time in the new business, such distant start-ups would pose new creative challenges.

the future, there are different ways the Association could develop. While this structure has done well for us, it has also been a creative experiment adapted as needed. Our current strategy is to saturate the Bay Area with the one business model, as it is the most efficient use of our still-limited resources. However, the market for neighborhood bakeries is not unlimited. Before we are able to sense such a limit, the member bakeries themselves will probably choose to restrict replication, in order to protect their perceived territories. Some members envision selecting another business model to replicate. Others envision reaching a critical mass of bakeries such that we might create jobs vertically - a flour mill, for instance, or an equipment maintenance team, or even a lending institution to offer capital to new developments. In another vision the Association would replicate itself and begin to create Arizmendi Bakeries in another city ? but because the efficiency of our support services increases with our density, and because trainers for new developments have historically worked part-time in their own cooperative and part-time in the new business, such distant start-ups would pose new creative challenges.

Steps for Replicating a Worker Cooperative using the Arizmendi Association Model

Our Association's steps to starting a cooperative differ in some ways from those outlined by popular worker cooperative organizers' guides. Perhaps the most significant difference is that much of the groundwork for the new cooperative is laid before members are recruited. This would appear to contradict the need to inventory members' skills, objectives, and economic needs to assure that the cooperative will benefit them. To make this leap, we assume there are pools of potential members whose abilities and needs match those that the cooperative requires and offers. Because of the density of our urban area and the high competition for decent-paying food industry jobs, this leap has been easy to make. While it is still important to include founding members of a new co-op in decision-making to foster group cohesion and democratic initiative, for the sake of efficiency the Association makes some of the early business decisions for the new co-op. For example, in our first replication founding members worked together to discover and negotiate for a location. In the development now underway, the location will be established before members are recruited.

Below, our replication process is loosely laid out in steps, intended as a rough guide for those who might like to use our model. The process is based on a long-term vision but has evolved improvisationally over time. Our cooperative association model will inevitably be refined according to the needs and desires of the member cooperatives that govern it.

- Establish an organizing group. This group will facilitate replication, but will not necessarily own the developed cooperative. In our current case the organizing group, the DSC, started as a volunteer study group. The DSC still works only part time on development, as our financial capacity to start a new business is not constant. One of the four of our current group has worked in a member bakery; the others have legal, financial, and organizational expertise.

- Choose a business model to replicate. This involves not only choosing the right cooperative business, but also convincing its members to allow you to replicate it. What's in it for them? Would the replication compete with their business? Would it increase their visibility and therefore revenue? Is there any financial return? In our case the Cheese Board had the financial strength to request very little in return. The creation of more democratic jobs did align with their values, and the Association can now offer support services to them, but their willingness was primarily an act of solidarity and generosity. For other replications, including future business models the Arizmendi Association may pursue, the organizers may not be so lucky.

The business model we chose has many good things going for it. One was that it entails a lot of customer service, an area in which worker-owners out-perform employees, often establishing lasting relationships with customers. The product is high quality and relatively inexpensive, helping generate a large customer pool by word-of-mouth. The model can be replicated many times in the Bay Area before saturating the market. Morning bakeries function as neighborhood civic spaces, which reinforces the community spirit of the collective. One downside was that sale of imported cheeses brings lower returns than bread, and requires more intensive training. Because of this cheese sales were all but eliminated in our replications in favor of pizza, bread, and pastries. Another downside of this business model is that it does not create a large amount of jobs. Each of the five Arizmendi Bakeries is owned by around 20 members

- Decide what relationship the new cooperatives will have to the older co-ops. Our model is described above, but our structure has not come about without some challenging questions. Who will own the replicated businesses and the debt of their startup loans? What will their relationship to each other be? How will the replication process be funded, and how can this funding continue or escalate over time? What incentive is there for the new co-op to stay involved with the ones that generated it?

The Arizmendi Association model uses the analogy of an "upside-down franchise." The new cooperatives stay involved because they are offered the kinds of services most efficiently provided centrally: financial, legal, educational, and other technical assistance services. The cooperatives govern and define these services, determining the rate of fees they contribute. Owned independently, the cooperatives are given the autonomy to adapt creatively to their needs. As owners of their own debt, they have incentives to make their business succeed. Meanwhile, non-debt development expenses are covered collectively by the Association and fees are contributed, in part, to perpetuate the development cycle. As more members come in, resources to create more members also grow.

- Set up the "turn-key" operation. In preparing to open a new worker co-op, the Association incorporates the new co-op prior to recruiting new worker co-op members. Thus, members of the Association are temporarily also the membership and officers of the new co-op. They must find a site for the new business and acquiring capital from a bank or a group of individual lenders in order to buy equipment and renovate. Getting a bank to lend to a business whose real members are not yet known can be difficult, and because the Association does not own its member cooperatives, it has little collateral to offer banks as security. Our track record and the social missions of the lenders we have worked with have helped to overcome this obstacle. For a new Association without any track record, lenders within the worker cooperative community may be needed.

- Recruit and train new workers. We recruit new workers during renovations about six months before the anticipated opening. The recruiting committee is made up of veteran members of existing bakeries. For the first months we do weekly organizational trainings, and several of the new workers are placed in internships at the existing bakeries. Working committees are formed during this time to do marketing, establish relationships with venders, and prepare other aspects of the startup. Once renovation is completed, new workers will train in baking bread for about two months before the store opens.

Our training team is made up of bakers from the existing member businesses. These bakers will work part-time at their home bakery and part-time in the new development. Having a pool of trainers available part-time every few years when development is in motion is a great resource, eliminating the need to hire an external team. The trainers oversee new members' work, working alongside of them for as long as six months. They demonstrate best practices in production, and set the tone of shop-floor communication and problem solving. We often think of this as a "sourdough" method of education: the culture of the veteran workers is the "starter" that creates the flavor and structure of the new workers' culture. Toward the end of the training period, the new workers will form a committee to recruit replacements for the trainers, who return to their home bakery.

- Repeat. Every replication will teach valuable lessons about what to do and not to do. Make sure to have a good evaluation of the process which included the views of the developers, the training team, and the new cooperatives members. Consider the long term as you hone your process.

Challenges

It has been a slow journey. Originally, the organizers of the Association had hoped to develop a new bakery once a year. Instead it has been at around a quarter of that speed. Our model has been very resource efficient, but has a slow growth curve. For many years only the first replication was contributing significantly. The Association staff, the DSC, could only afford to work very part-time or as volunteers. A decade later, three member cooperatives are now contributing significant fees. As we grow into a more robust organization, our former lean years will seem more and more foreign, but for organizations following in our footsteps adaptations may be available to accelerate the development process.

| Conclusion |

The replication of the Cheese Board Collective model into three Arizmendi Bakeries (with a fourth in progress) has been successful. All of the businesses are profitable and have support services ready should they falter. The quality of the food is high, earning multiple critic and reader awards in the local press. The average labor compensation is almost twice the industry average. Worker turnover is low. The original generosity of the Cheese Board and the excellent business model they offered (which itself was refined over several decades) has helped put the Arizmendi Association in a good position. We will continue to replicate bakeries for the next several years, and when we reach a saturation point we will adapt and innovate.

Joe Marraffino is a cooperative organizer for the Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives, a network of worker-owned bakery cooperatives in the greater San Francisco region of California. He is also a worker-owner of the Arizmendi Bakery in San Francisco. He is a board member of the California Center for Cooperative Development, and former board member of the Network of Bay Area Worker Cooperatives. He has a Master's degree in Culture, Ecology and Sustainable Community.

Marraffino, Joe (2009). The Replication of Arizmendi Bakery: A Model of the Democratic Worker Cooperative Movement. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume 2, Issue 3, http://www.geo.coop/node/365

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License.

Association of Arizmendi Cooperatives

1904 Franklin Street

Oakland, CA 94612-2912

(510) 834-4221

www.arizmendi.coop |

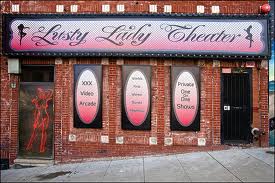

Lusty Lady Theater of San Francisco

Under Nude Management

by David Steinberg

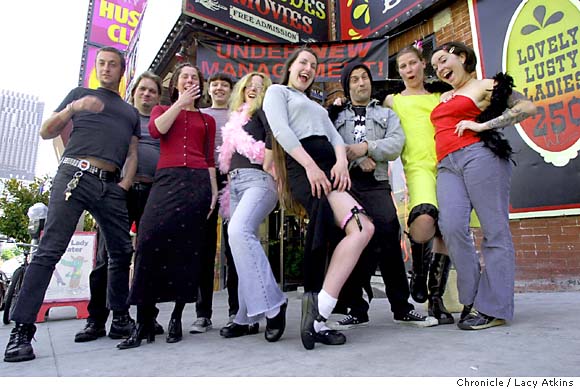

The strippers and support staff at San Francisco’s Lusty Lady peep show theater had done it again.

After months of hard-nosed negotiations — including three days of eye-catching informational pickets and full preparation for a strike — the workers at the only unionized sex club in the nation got just about everything they wanted from the theater’s owners — restoration of an earlier $3-an-hour pay cut, a cap on the number of dancers working at the theater, an end to videotaping dancers while they worked, and no back-tracking on sick days and health insurance.

It was a hard fight, and the dancers were heady with victory. For the sixth time since they joined Service Employees International Union Local 790 in 1997, the dancers had held their own in a contentious labor dispute and proved to the theater’s owners, to themselves, and to the world at large that women who dance naked for a living could stand together, fight for what they wanted, and win. Coming down to the wire about calling a strike (contract agreement was reached three days before the strike deadline) had forced everyone to pull together, get organized, get clear about their priorities, and get efficient. If they had doubts before, the dancers and support staff at the Lusty knew now that, when the chips were down, they could meet, make decisions, and pull together to do what needed to be done.

If you think that women who strip naked for the sexual pleasure of others — who display their bodies only inches and a thin sheet of plexiglas away from hundreds of masturbating men each day — must be pitiful souls devoid of pride or self-esteem, think again. The 60 dancers and 15 support staff at the Lusty Lady Theater are a strong, energetic, and creative crew. And they’ve discovered that, with a union to back them up, they don’t have to accept wages and working conditions dictated by the people they work for. They may not get everything they want, but they usually get pretty close. Most significantly, they know that they can be active players in the workplace, rather than powerless pawns being moved around the chessboard by people and interests far more powerful than themselves.

In this case, however, despite their contract victory, it soon became apparent that all was not well in paradise for the Lusty dancers. Less than two months after the new contract was signed, dancers and staff at the Lusty were notified by the owners that the theater was going to close up shop in three months. Darrell Davis, the company’s general manager, tired of flying from Seattle to San Francisco to deal with labor issues, had resigned and, perhaps as a result, the owners had decided to dump their San Francisco franchise and relax into the more placid business of managing their Seattle theater, where non-union dancers accepted management’s rules without serious question and kept any grievances they might have to themselves.

The owners had warned during contract negotiations that, if they gave the dancers what they wanted, the theater would no longer be profitable. But the owners had said the same thing each year during contract talks, and the dancers didn’t believe them, especially when the owners refused to let negotiators examine the company books. But this time the owners weren’t bluffing and everyone’s worst-case scenario had become a reality. The owners wanted out, there were no buyers who wanted to take on the “liability” of dealing with a union, and everyone was about to be out of a job.

During negotiations, Donna Delinqua (her stage name) — a graduate student in English Literature who’s completing her dissertation on the depiction of sex between women in pornography — had not entirely dismissed the owners’ claim of impending financial insolvency. But Delinqua wasn’t intimidated by the possibility of a shut down. “If they close the theater,” she thought, “we can just take it over.”

During negotiations, Donna Delinqua (her stage name) — a graduate student in English Literature who’s completing her dissertation on the depiction of sex between women in pornography — had not entirely dismissed the owners’ claim of impending financial insolvency. But Delinqua wasn’t intimidated by the possibility of a shut down. “If they close the theater,” she thought, “we can just take it over.”

It wasn’t the first time the idea of dancers running the theater had crossed someone’s mind. Three years earlier, a group of dancers considered buying the theater if the owners made good on their threat to close the place down. Now it was time to see if the idea of a dancer-run strip club was just a pipe dream, or if the idea could be transformed into workable reality.

Delinqua called a general meeting of dancers and staff. Rainbow Light, a well-established local grocery cooperative, and Good Vibrations, the nationally-known, women-friendly, worker-owned sex toy store, sent people to explain the nuts and bolts of structuring and operating a worker-run business. The idea of actually owning the place where they worked was exciting and infectious, and the we-can-do-anything feeling from the triumphant contract negotiation was still very much in the air. The group decided to put together a plan to buy and operate the Lusty Lady themselves.

“If we hadn’t just come through the negotiations,” says Ruby, who has danced at the Lusty Lady for a year and a half, “I don’t know if we could have made this happen. But we had become a strong group, we had gotten used to working together, and we just believed that it was possible to buy the business and make it work.”

Plans were developed, organizational and operational structures hammered out, committees formed. Pepper was in charge of negotiating the purchase with the owners. Tony would come up with a financial overview. Miss Muffy would coordinate signing people up as owners. Ruby would deal with the city, the police, and the fire department about licensing. Havana would take charge of getting the new business incorporated. Rapture and Cayenne would write the new corporation’s by-laws.

In less than three months, everything had come together and on June 1 the Lusty Lady became the nation’s first worker-owned strip club. General manager Davis, who had stirred intense anger among dancers during contract negotiations, became noticeably cooperative when it came to negotiating a buyout. It didn’t hurt that the dancers’ was the only offer on the table. A selling price — confidential, but substantial — was agreed to and, if all goes well, will be paid off over the next five years. There was no down payment.

Anyone who works at the theater can become an owner for $300, regardless of how many hours they work. “We wanted to make the amount people paid to become owners large enough that it be a real commitment,” Delinqua explains, but not so much that it was out of reach.” To make becoming an owner accessible to as many people as possible, the $300 can be paid over time. At the end of each fiscal year, any profits above money reserved for working capital is to be distributed to owners, based on how many hours they’ve worked. Of 60 dancers, 45 have already become owners, with more expected to sign up over time.

The company’s Board of Directors is made up of five dancers and two support staff. After years of feeling pushed around, the dominating ethos is a commitment to fairness, cooperation, and equality. Decisions are made by majority vote, “but we use a consensus-building process to try to make sure that everyone’s concerns are dealt with,” Delinqua explains. The Lusty’s ground-breaking union, however, has not been disbanded. “There’s no guarantee that, down the road, people will be as committed to fairness as we are,” Board-member Pepper notes. “Also,” she adds, “we want to continue our outreach to other strip clubs about the possibilities of unionization.”

As it turned out, many of the dancers had skills that proved useful in pulling the new cooperative together. Some had worked as paralegals. Others had managerial experience. Mostly, though, it was a matter of rolling up your sleeves and discovering that you could do things you’d never done before.

“It’s been a huge learning curve,” says Ruby. “Before this I didn’t know anything about running a business. We’re all learning about accounting procedures, about insurance — things I never thought I’d be doing when I signed on as a stripper.”

The difference between working for someone else and working for yourself is like the difference between night and day, especially in a service business that rises or falls on the personal appeal of its workers. Two months into their experiment, the dancers at the Lusty seem almost universally excited about their new possibilities.

“We’re about to see a new Golden Era at the Lusty Lady,” Pepper predicts. “The importance of worker incentive should not be underestimated. Now that we’re working for ourselves, everyone feels fresh and friendly, and that affects how we relate to each other and how we relate to the customers. Now everyone has new reasons to be present with customers, to give good shows. The quality of everyone’s performance is going up. The theater is cleaner than ever, and we’re considering a number of capital improvements, like new carpeting.”

“All the stuff that used to be secret and shrouded in mystery,” says Ruby, “now it’s posted every week, open for everyone to see. How much money we brought in, each check that was written, how the Private Pleasures booth did.

“People seem to be getting into being more glamorous, getting more elaborate with their costumes, paying more attention to their appearance than they were before,” Delinqua notices. “Now everyone has to consider the financial consequences of what they do, how they act, how they look.”

Delinqua points to the new system of dancer evaluation as one concrete example of how things have changed with worker ownership. “Before,” she says, “dancers were evaluated by managers who were not dancers themselves. Now, it’s all peer evaluation. Each week a new group of five dancers evaluate the other people on their shifts — their general appearance, being pleasant with the customers, making eye contact, paying attention to the customers, making them feel welcome. There are no managers, only team leaders — we call them Madams of the House — elected for six-month terms. Everyone dances.”

Ruby likens the new spirit at the Lusty to the pioneering example of Good Vibrations. “Good Vibrations totally changed the world of sex toy shops,” she notes. “Before Good Vibes, sex shops were seedy places. Women didn’t go there. Good Vibes changed all that. It’s clean, it’s not creepy, so going there is no big deal.

“We’re trying to do the same thing. We want to show that it’s ok to view adult entertainment, that it doesn’t have to be something you’re ashamed of, something you do in secret. We hope to include women customers more, and to make everyone feel more comfortable coming to the theater.”

The sense of new beginning is tangible everywhere around the Lusty. People are realizing that, now that they own their own business, they can do what they want with it, and new ideas are cropping up everywhere. The first major innovation was the establishment of Women’s Night, which will be the last Wednesday of every month. The first Women’s Night in July was a huge success — grossing 20% more than usual for a Wednesday. (Men were allowed, if accompanied by women, but they had to pay $10 at the door, and stay with the women who brought them.)

“We set aside half the booths for women only,” Delinqua explains. “We made sure that everything was very clean. We had dancers meeting women at the door, acting as their Lusty Lady Tour Guides, helping ease their transition. About a hundred women came. The dancers were so excited to be bringing women in. Good Vibrations and S.I.R. Productions sent gifts of lube, porn, and condoms. The evening was co-sponsored by the Sex Worker Film and Video Festival. Everyone had a great time.”

Another new idea being considered is having a couples night, where a woman could come with her husband, boyfriend, or girlfriend, go backstage, get glammed up with the help of regular Lusty dancers, and then dance on stage for her partner — a chance for women to act out the fantasy of being stripper for a night. A perfect birthday gift for a partner, or for yourself.

“We want to be innovative,” Delinqua says. “We want to try new things and see what works. There’s the sense that we don’t have to be bound by how things have been done before.”

So far the new system seems to be working well. Delinqua estimates that about a third of the new owners are actively involved in running the business. Some potentially difficult issues — discipline, hiring new people, long-range financial decisions — have yet to come up, but Delinqua feels confident that these issues can be dealt with constructively, in the spirit of cooperatively working together.

“Most people feel vested,” says Ruby, “and that makes all the difference. It’s our show now. It’s a really exciting time for all of us. We’re all here doing it together and we’re really proud of what we’re doing. We’re trying to make the Lusty Lady a safe and fun place for everyone — dancers and customers alike. And we hope that we can inspire other sex workers to know that you really can do it yourself, especially if you have a strong group of people committed to working together.”

© 2003 di David Steinberg

www.davidsteinberg.us

Lusty Lady Theater – 1033 Kearny Street

San Francisco CA 94133 – USA

In 2006, Andrea Papi wrote on the magazine “A” highly critical considerations on the Coops made in Italy. The editor of the dossier on the “Coop made in the USA” has suggested their re-publication here. Because in Italy the cooperation has a long history that can teach to everybody very much.

Harnessed cooperation

Proudhon and Owen

The first cooperative in modern memory, who has lived its activity in the textile industry, dates back to England in 1844 in Rochdale, north of Manchester. What is important to note is that the "honest pioneers", as they were defined these early co-workers, got together to start an alterative forms of private enterprise or government. Shortly after, in the decades of the second half of the nineteenth century, in Italy and France, we have the rise of the first forms of association in the form of “mutual aid companies and banks”, founded to rise both to remedy the deficiencies of insurance laws and social protection of workers, both to build up the active forms of self-managed workers' solidarity. In Italy the first were inspired by the republicans, in France by Proudhon. The cooperative experience at its rising, therefore, was designed and invented by the workers to create alternative economic structures different from both private and state structures, that was an invention with revolutionary intent and content.

But from the beginning of setting contained unresolved hybrids which could hardly be noticed and dealt with by their founders. On one side was certainly a useful tool for testing the construction of new relations of production, not subservient to either the capital or the state but managed by producers. On the other side it could well be a way to manage non-privatized production but always within the capitalist system, potentially, they could be used to absorb the conflict while maintaining cooperation perfectly inside the logic of the market and competitiveness. Everything depends on the level of awareness of its protagonists and the realization tension they are willing to put in place.

This dichotomy is also reflected in the theoretical analyzers. On the one hand we have for example Owen and Proudhon, who emphasize the values of tolerance and overcoming of the capitalist logic of profit, of emancipation from exploitation of the workforce, and realization of self-organization worker solidarity and equality.

On the other hand however we have for example Stuart Mill, who captures only the different way of organizing the production and cooperation which leads to the bed of an optimization of the division of labor, or Vilfredo Pareto, who perceives it as a form of hybrid between socialism and capitalism, as well as highlighting the corrective capacity of the capitalist defects resulting in improving the degree of competitiveness of the private sector.

No coincidence that throughout the second half of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth century it was widely used by all members of the labor movement. For anarchists, Republicans and revolutionary federalists syndicalists it was conceived as a revolutionary means of emancipation from exploitation and breeding ground for construction of the new society, for the radical socialists and social democrats as an essential tool for the victory of the socialist reform.

The fascist movement provided then finally to smash it, as this represented a threat to the conservation of the system. In 1926 he dissolved political parties and opposition newspapers, banned the existing co-operatives by closing their offices and destroying their tracks, and founded the National Fascist Institute of Cooperation, depriving cooperation of its autonomy with state interference.

After the liberation in 1945 the cooperative movement regained form and force, but was completely deprived of the radical and subversive inspiration that had marked the birth and the entire process of social construction of pre-fascist era.

Accomplices the reformist parties of the labor movement, it has ceased to be a basis for the construction of an alternative possibility for a new society liberated from exploitation and oppression, adopting almost entirely the logic of classical type of capitalist management.

It remained the same in the ownership structure (the members all have the same number of shares), but no longer exists, except in very rare cases at the margins, the collective and community management which is today tout court entrusted to the internal management of the boards of directors. The moment you switch between forms of self-management type to forms of business management, you cancel the substantial differences that determine the diversity of political equality.

The crisis of the "good comrades"

Cooperation has now become in full an integral part of the system of capitalist production, which unlike its original purpose and its genes would help to break down and overcome, and aspires to become a strong component, capable of competing in the market and to grab their slice of profit and substantial financial flows in global scope. It is now just a different technique of production organization, without being anymore an alternative way of organizing social relations and production.

In other words, Mill and Pareto fully won and Owen and Proudhon lost. ...

There are no means or instruments, as coherent and consistent, which as such are able to make the transformation, especially if we assume for emancipatory and revolutionary. If you are not supported by adequate awareness, they alone are insufficient to lead to the end. As they always contain, and can not limit it, the potential to be recovered and approved by the system against which they were designed, if they are not sustained by a strong will and awareness to achieve the intended purpose, the end may be deviant.

Andrea Papi

Andrea Papi

from “A” 315 (March 2006)

Note from the translator, Enrico Massetti:

Benjamin Franklin said that democracy is guaranteed by the democratic system of government that the United States gave itself only as long as everybody will stay on guard to protect it. The concept definitely applies also to democratically-run worker-owned coops.