|

|

An architetture and building co-op in Montana that uses recycled and build eco-friendly buildings

Big TimberWorks Homes |

Cooperatives are part of the self-help tradition of America. Cooperatives are businesses organized by people to provide needed goods and services. Cooperative businesses:

• Are owned by the people who use their services;

• Provide an economic benefit for their members;

• Are democratic organizations, controlled by their members;

• Are autonomous and independent;

• Recognize the importance of education about cooperative business and organizational practices;

• Support cooperation among cooperatives, which has resulted in the growing importance of cooperatives in today's global economy; and,

• Exhibit concern for their communities.

Cooperative businesses provide just about any good or service their members need. Cooperatives offer credit and financial services, health care, child care, housing, insurance, legal and professional services. Cooperatives sell food, farm supplies, hardware and recreational equipment. They provide utilities, such as electricity, telephone and television. And cooperatives process and market products and goods for their members.

| From Michael Moore film “Capitalism: A Love Story” |

...I don't know much about politics, I have been part of Union Cab of Madison Wisconsin for 21 years, I wouldn't have stayed around so long if it wasn't for its structure....

Fred Schepartz, taxi driver, Madison Union Cab

... I have a PhD in antropology, so I love to see people behaviour. The first ten minutes I was in a cab I asked myself "what I have been doing wasting my life not driving a cab?"... I can expect to make between 18$ and 26$ an hour... we are the most succesful cab company in Madison, and this is in part due to the fact that we don't have to pay the CEO a six figure salary... I think our name, Union Cab, is beautifully evocative of how we are as a company,... we have repubblicans, we have democrats, we have socialists, we have anarchists,well, I don't think we have any communist...

Rebecca Kemble, PhD, taxi driver, Madison Union Cab

|

Co-op Types

Cooperatives are categorized in two ways: by type and sector. Cooperative "types" are based on their ownership structure and function. The two main types are consumption and production, and each of these can be organized among individuals or organizations.

Consumer co-ops may be formed by individuals or businesses, and in the latter case they are often referred to as "purchasing" or "shared service" co-ops. On the other hand, producer co-ops include both those formed by businesses – often called "marketing" co-ops – and "worker" co-ops whose members are individuals. Some co-ops are hybrids, combining elements of more than one type of co-op.

Each type of co-op has many subcategories and some co-ops contain elements of both types. For example, an electric cooperative falls into the consumer type because the consumers in the service area of that electric co-op own it. Of course, many businesses are also members of electric co-ops. However, in some cases electric co-ops and other utilities form purchasing co-ops to generate or purchase the power they distribute to their members. This is sometimes called a second-level co-op, federated co-op or federation.

A map of the 200+ worker cooperatives in the U.S., and some other movement organizations

(map by Joe Marraffino)

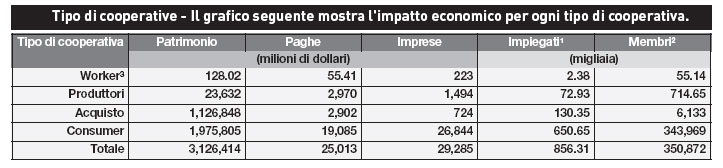

The chart below shows the economic impact for each type of cooperative.

Worker Cooperatives

Worker Cooperatives

Worker cooperatives are businesses that are owned and democratically governed by their employees. They operate in numerous industries, including childcare, commercial and residential cleaning, food service, healthcare, technology, consumer retail and services, manufacturing, wholesaling and many others. Some 300 worker co-ops throughout the U.S. provide their employees with both jobs and ownership—allowing them to directly benefit from the financial success of the business. Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) are a more common form of worker ownership in manufacture, although they often lack the democracy inherent to co-ops..

Democratic governance

Like other cooperatives, the board of directors for a worker co-op is elected by, and from within, its membership-in this case, the workers. The board is always majority controlled by the workers, though some worker co-ops have outside directors and advisors serving on their boards.

Management structures of worker co-ops vary greatly, depending on the desires of the members. Some worker co-ops use a traditional management hierarchy, while others use more flat management systems – often called collectives – that allow employees to be more directly involved in management decisions. Others use a team-based system that employs elements of both traditional and open management systems. Many worker cooperatives use a consensus process that seeks decisions that have the consent of all members, so even a single person can block a proposal.

Profits and Wages

Profits and Wages

Each year, worker co-ops return profits to their worker-owners in the form of patronage dividends. Dividends are typically distributed based on hours worked, salary and/or seniority.

Pay structures vary greatly. Some worker co-ops use a traditional, position-based pay scale. Others pay strictly on seniority. At the other end of the spectrum are worker co-ops that pay all workers the same wage.

Joining a Worker Co-op

Typically, workers may join their co-op after a probationary period lasting from a few months to more than a year. At that time, workers are accepted as full members, often by vote or consensus, and buy an equity share in the business—the cost of which is usually deducted from their paychecks in small amounts each month. When workers leave the co-op, their equity share is returned to them.

Some examples of worker Co-ops using a flat management system:

This first dossier wants to illustrate some of the different realities of worker-owned cooperatives that are closer to the libertarian cooperative concept, realities that are often not well known and/or understood outside of North America.

Watch the video: Democracy on the workplace

| The New World Order (at least until January 2013) |

3 January 2011

Today, across the nation, the Republican Party took control (or partial control) of a number of statehouses, the House of Representatives and governor mansions.

It would be easy to mourn this event. It is tempting to protest.

The reality is that this is our reality for the next two years when the voters might throw all the bums out again.

For cooperatives, it creates opportunity. In Wisconsin, Governor Scott Walker (Republican ndr) declared that Wisconsin is open for business. Why shouldn't that business be cooperatives?

My reality over the last couple of years has been that the Republican party and the so-called conservatives have been very receptive to my coop. They see us as a business, as entrepreneurs, as the very fabric of the USA that they like.

From the blog Rochdale |

Some Coop made in Usa

Collective Copies, Amherst, MA

"Nothing worked"

"Nothing worked"

One employee summed-up the problems of the late Gnomon Copies in this way: "The space was tiny, the air quality was terrible, the pay was lousy, the machines didn't work half the time, and management just didn't care." In mid 1982, workers at the shop decided to take steps to change the situation; they organized; they unionized. By the end of that summer, they walked out.

The strike dragged on through the fall, with workers collecting strike pay — a fraction of their already low pay. One employee got through the season on the fish he was able to catch from local streams and by frugally darning his socks on the picket line. The rest of the striking workers found other forms of local sustenance; the Amherst community solidly supported the strike, local residents joined the picketers and boycotted the shop, and a handful of area journalists made sure the strike wasn't neglected in the press.

A resolution squeaked through just barely ahead of the winter. Then, days after negotiations were successfully concluded, Gnomon was given an eviction notice. By mid-December, the strike was finished . . . and so, it appeared, was the shop.

... Then, in march of 1983...

a new copy shop opened in Amherst. Pooling their skills & experience, the old Gnomon workers launched their own shop above Wooton Books. The space was tiny, the air quality still wasn't great and the copiers sometimes seemed nearly as close to collapse. But the shop that emerged from the preceding autumn's strike was owned by its workers and run collectively.

Twenty five years later, Collective has changed: entirely digital and with triple the original staff and three stores around the valley, the business has thrived: the community has come to rely on our quality and civic involvement, and the workers benefit from a workplace that values and rewards our work. What has not changed is our commitment to our founding values and to providing an example that those values work.

| Cooperative structure |

Collective Copies was founded as a worker-owned collective co-op in 1983..

What's the difference between a co-op and a collective?

The short answer is that a collective is just one form a co-op may take. A co-op may be constituted along any of a fairly familiar range of structures: straight hierarchy; a management team and a labor force; democratic or participatory management or, as in our case, a collective. The collective structure is characterized by consensus decision-making; we do not have separate management or labor teams. We all do more or less the same job (see below for details) and share administrative, managerial, customer service and production responsibilities and so we run the business on the basis of our shared experience and expertise.

Who's the manager in a collective?

A collective doesn't really have a 'boss' — it runs counter to the collective philosophy. In some collectives, there may be a member whose task it is to act as office manager, another who does bookkeeping, another who purchases inventory...each of which in a traditional business might be regarded as a managerial position but, in a collective, these tasks are usually distributed among numerous members, based on skill and inclination and in such a way as to avoid a power imbalance.

How do you decide what to pay yourselves -- benefits and such?

We're the owners as well as the workers; while this presents sometimes competing instincts, our decisions are ultimately based on what we'd like, what's fair, and what's good and reasonable for the business. One of the incentives to be responsible in this area is the year-end distribution of profit shares; if spending has been high, we have little to distribute at year's end. If investment in the business has been too low, profits will diminish over time. It helps that over half our members have 9 years or more in the collective -- we have a long view.

How does the business management end of things get done? (Who pays the bills?)

Again, each collective will approach this in their own way. In our case, in addition to our usual daily work, each of us takes on administrative tasks on the basis of skill or inclination. At one time, each administrative task could be performed by a single individual. These days, most require the work of a committee. We break down the administrative areas as follows: Accounts payable, accounts receivable, financial, supply ordering, paper ordering, marketing/promotion, donations, accounts development, payroll/vacation, sales tax, benefits administration, machine maintenance & repair, new equipment & services research, health & safety, aesthetics and physical plant. At certain times of the year we add copyright clearance.

CollectiveCopies

http://www.collectivecopies.com |

|

The Green Mountain Spinnery, Putney, Vermont:

a spinnery |

Si se puede! Brooklin, New York

Si se puede! Brooklin, New York

In 2006, Latina immigrants in Brooklyn, N.Y. formed a housekeepers' co-op to avoid exploitation, according to Vanessa Bransburg, cooperative coordinator of the Center for Family Life (CFL). With the help of the community organization, 19 women from Mexico and the Dominican Republic formed We Can Do It!, or Si Se Puede!, a slogan used by organized workers in Latin American and California.

"A lot of these people really had the entrepreneurial spirit, but a lot of them don't have up to high school education, so they weren't able to get a traditional job," said Bransburg. "Instead of following somebody else's rules, they wanted to be the bosses."

Eleanor J. Bader comments: "Five or so years ago, CFL was running a traditional employment center, helping people prepare resumes and go on job interviews," says Vanessa Bransburg, CFL's Coop Coordinator. "As the economy began to tank, staff noticed that it was getting harder and harder for people with language barriers or undocumented status to find work. One CFL worker began investigating coops and started chatting about them in an ESL class. Most of the women in the class were already attuned to the idea of cooperative work; they knew about the artisan coops that exist throughout Latin America and liked the idea of working together to build a business. It was clear that most of them wanted to work, rather than rely on their husbands or partners for money. And most of them already had experience cleaning houses and offices."

The idea of a women's cleaning coop swiftly took root and together with CFL staff, the participants chose the name Si Se Puede! and developed a 10-week curriculum to prepare themselves for starting the business. Classes covered rudimentary skills—from how to provide high-quality customer service, to doing publicity and promotion, to using the most effective and least toxic cleaning products. They also tackled more complex themes, from the nuts-and-bolts of democratic governance to analyzing different models for working cooperatively. Along the way they found an important ally—the Urban Justice Center—whose lawyers helped them draft and finalize bylaws and, later, incorporate as a not-for-profit cooperative corporation under New York State law.

The coop now has 28 members, all of them immigrants from Bangladesh, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. Each pays a $40 monthly fee for administrative expenses—including childcare and snacks during weekly meetings. While this fee is expected to increase once the coop hires an office manager/scheduler, members like Cristina say that the dues are a small price to pay for what is received. She needs no prompting to sing Si Se Puede's praises. "Now, thanks to the coop, I have jobs that take me three to five hours to complete," Cristina says, "and I make the same amount I used to make for 12 hours of work. I can also control my hours, which has been the biggest benefit, especially now that I have two children. Plus, I've gotten so much help from other coop members. I don't have any family in the United States so the other coop members have become my family."

At the same time, like all coops, membership in Si Se Puede! requires participation in the day-to-day management of the business and there is work to be done beyond the payment of dues. For one, members must spend three hours a month promoting the coop to potential clients. This might mean staffing a table at a summer street fair or handing out Si Se Puede! literature in upscale Brooklyn neighborhoods.

This old-fashioned, grassroots outreach has paid off; the coop now has more than 1,300 people in its database—from one-time users to weekly clients. What's more, they've scored work not only from individuals but also from yoga studios, stores, and a Fort Greene bed & breakfast.

In addition to doing outreach, members are also required to attend weekly meetings where business decisions are hashed out. Some meetings are devoted to skill enhancement—and have included training in time management and health and safety. Since decisions are made by consensus, Bransburg admits that the meetings often run long so that issues can be fully addressed.

Current hot topics include how fast Si Se Puede! should grow. Should membership be capped, so that the coop remains small, or should it be opened to new members? If they choose to expand, will increased numbers inhibit participatory democracy? Can they avoid a more traditional hierarchical structure if they double or triple in size?

Not easy questions, these, but Si Se Puede! members and CFL staff agree that change is inevitable if the coop is to continue to thrive, and all are confident that the business is strong enough to weather growth spurts and challenges. In fact, [Cooperative Coordinator Vanessa] Bransburg says that interest in the Si Se Puede! model is burgeoning and groups like Make the Road New York and Catholic Charities are looking to CFL for help in establishing similar projects in other parts of the city

We can do it! Si se puede has been a worker-owned cooperative since 2006.

The Center for Family Life in Sunset Park acts as their agent, with 100% of the cleaning fees going to the workers, who pay $40 in monthly dues to cover marketing costs. The organization has spun off two other worker co-ops: Beyond Care, with 19 child care workers, and Émigré Gourmet, a cooking collective.

All the worker-owners have equal control over marketing and they develop their own relationships with their clients, said Bransburg. "With all of this happening, they've been able to withstand the recession and even grow in the last few months," she said.

We can do it! Si se puede!

http://www.wecandoit.coop/

|

Cooperative Home Care Associates, New York:

a coop of 1,600 nurses providing home care in New York . |

Arizmendi Bakeries, San Francisco, CA

Arizmendi Bakeries, San Francisco, CA

"I love saying to people that this seems like an impossible business model, but it works, and it works very well."

Charlie

(Longtime Cheese Board member)

The Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives is itself a cooperative made up of eight member businesses: six cooperative bakeries, one cheese store and a development and support collective. Members share a common mission, share ongoing accounting, legal, educational and other support services, and support the development of new member cooperatives by the Association.

These worker-owned bakeries in the San Francisco Bay Area, took their name as well as their business plan from Mondragon, the Co-op system from the Basque country. The companies share technical and financial resources — as well as proprietary recipes — and a portion of profits goes to funding new enterprises. The notion of cooperative artisan bakeries sounds quaint, but the group is thinking beyond the breadbox. "We consider this the very beginning phase," says Melissa Hoover of Arizmendi, who is also executive director of the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives. She says the companies plan to develop more businesses and are researching possibilities "along the supply chain": trucking, retail, health and wellness, as well as a funding vehicle like Caja Laboral, the banking system of the Mondragon coops.

Arizmendi now employs 125 workers and annually generates $12 million in sales. Despite the economic downturn, the businesses remain strong and poised for growth. This in part owes to the collective decision-making model, says Hoover. "Worker-owned cooperatives are an innately conservative form. We didn't overleverage ourselves."

The belief that every voice is central has sustained the members of the Arzimendi coops over the years. They have never wavered from the original vision of a democratic workplace. This commitment has made it possible to constantly reinvent themselves, while remaining faithful to their political vision, and their belief in good, honest food.

Cooperative structure and history

The Arizmendi Bakeries are structured as independently owned and managed bakeries, that share one central company for research and development, the Arizmendi Development and Support Cooperative (or DSC), that is the internal staff collective for the Arizmendi Association. The DSC provides financial, legal, organizational, and educational support to the members of the Association. The DSC also coordinates the development of new cooperatives. See how this is done at: http://www.geo.coop/node/365.

The Cheese Board opened as a small cheese store in 1967. In 1971, the two original owners sold their business to their employees and created a 100% worker owned business of which they remained a part.

The transition to a worker-owned and operated cooperative relied upon a shared work ethic, high standards, and the strong emotional connections among the group. Decisions were made, after much debate, either on the shift or at the monthly meetings. The new owners shared a belief that the collective process would organically create a truly democratic society. The Cheese store had a successful bread and pizza business, that was spun off as an independent co-op business, and later replicated to reach the current 6 bakeries across all San Francisco Bay area.

In each bakery the decision making, in addition to the day-to-day small decision that are done on the spot by the involved worker, and through shift decisions meetings. For the more important decisions it is democratically done through monthly general meetings, one worker-owner, one vote. The decisions are made through consensus, not through the majority of votes.

The collectives also apply the rotation of job assignments, in which every worker is assigned to every job, manual and intellectual, such as cleaning the floors to placing purchase orders, from baking to serving the customers, even if, in practice, it happens that people that are not comfortable with mathematics tend not to do the book-keeping, or people uncomfortable with dealing with customers tend to do the back-kitchen baking instead, but nobody is forced to do so.

Courtesy in part of the Cheese Board collective cookbook

Beyond the bottom line – An interesting video on the American Worker Cooperatives, on sale at Headlamp Pictures at: http://www.headlamppictures.com/html/beyond.html

Ecology Action, Austin, Texas

Ecology Action, Austin, Texas

Origins and Brief Summary of Ecology Actions

Ecology Action of Texas was founded in 1970 as an all-volunteer group that sought to promote a variety of environmental issues, most notably recycling. Today our mission is to educate and empower people to create a healthier environment through waste prevention and accessibility to recycling.

In 2000 we became a worker-run cooperative operated by a democratic decision making process. This horizontal structure has allowed for equal pay and sharing of the work loads, as well as for all of the employees voices to be heard in actively deciding what is best for Ecology Action. We are currently a union IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) job shop: Local Industrial Union 650. We believe that the way we operate our business , where our materials end up, and education are crucial to creating a sustainable and just world for all. We hope that the models we create will inspire other non-profits and businesses to re-evaluate their practices for the future.

What We Do Today

Ecology Action of Texas is a nonprofit, 501(c)(3) membership organization dedicated to public education and community service. Our mission is to educate and empower people to create a healthier environment through waste prevention, accessibility to recycling and cooperation.

We operate recycling drop-off centers across Central Texas and maintain a recycling drop-off and processing center in downtown Austin.

Future

Landfills aren't the only thing we impact. By using recycled instead of virgin materials, manufacturers are able to conserve resources and reduce pollution. The waste we diverted last year made a big difference to the quality of our air, water, and land. We recycled enough aluminum to save 232,000 kilowatt hours of electricity. The glass we recycled saved an equivalent of 4,432 gallons of fuel oil. The paper we recycled saved 16,924 trees and 6.9 million gallons of water as well as 3,285 cubic yards of landfill space and 4 million kilowatt hours of electricity.

Ecology Action

http://ecology-action.org

Photos by Ann Harkness

Firestorm Café and Books, Asheville, North Carolina

http://firestormcafe.com |

"...At the same time, some of us are also interested in pushing the limits of the infoshop model by embracing our role as an anti-capitalist business. Unlike a lot of infoshops, which try to exist outside the market in a sort of underground capacity, we are deliberately competing with capitalist enterprises. In part, this is a practical decision–too many libertarian projects go under because of financial pressures, volunteer burnout, and short sightedness. Working from a business plan, maintaining high standards, and compensating labor lends stability to the cafe and expands the range of people who can participate.

Additionally, the approach is influenced by a belief that anarchism can and should win ground by out-competing capitalism. Rather than cede economic territory to capital, we can contest it and demonstrate the effectiveness of cooperative economic principles while building momentum. Workers' cooperatives can provide us with both valuable resources in the present and a starting point from which we can begin to envision a libertarian future..."

from an interview to AK Press Blog

http://www.revolutionbythebook.akpress.org/store-profile-firestorm-cafe |