The funeral |

Ipswich, London,

Monday 1° March 2010 |

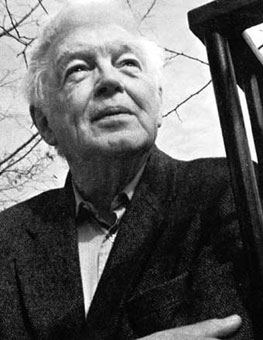

Colin Ward was an anarchist, a journalist, author of books on architecture, work, childcare, education, social history and many other important issues for those who aspire to a better world. He was a quiet man of great integrity, who had won the admiration and affection of readers around the world, and was one of the most influential thinkers of his generation.

At his funeral, on 1 March 2010, relatives and friends were invited to remember and their speeches are a first chapter of this short collection. On 10 July of that year was held in Conway Hall in London a Memorial meeting, and the second part presents the contributions on this occasion. Finally the booklet contains a bibliography of major publications of Colin.

Opening Address

Ben Ward

Good morning everyone. As you know, we are here today to celebrate the life of Colin and to greet him. I went with him to some funeral and he always said that these were happy occasions, opportunities to get together with friends and family. With this in mind, we organized a service that we hope Colin would have liked and we hope that you also make them smile a little.

Colin has lived in London until he completed 55 years (except for the five years of military service between 1942 and 1947) and the subsequent thirty years in Suffolk. So he did not move much. But his ideas, his spirit and his special personality have traveled far and wide.

One of his usual phrases, especially when he was offered a sandwich for lunch or as Harriet served a second time one of the delicious dishes that made him, was: "Think of others." For about an hour and ignore His exhortation 'll do to him alone.

I would like to invite George West to say a few words. For thirty years, Colin phoned George twice a week, but their relationship was not limited to this, as you shall hear.

Friendship with stable rhythm

George West

I met Colin in November 1950. We took the same route to go to the office, from the metro station of Gant's Hill, the Shangri-la of Essex. For sixty years we have enjoyed all of our complicated lives. Only poetry can capture the essence of a person, and I'm not a poet. My memories are not of summits and depths, but a friendship of stable course. Colin was a man who had no malice in him, no jealousy or envy. It was a good person? I can not say, but his actions were born from the same suit. That's how I see it now, at present, because we made each other and he's part of me.

The office where we worked was not large, about eight people who planned housing projects with commitment and passion. At that time in the office there was a certain enthusiasm to grow avocado plants. Colin and I thought of having to try too, and so the story began. We went to the close greenhouse, between Davis Street and Oxford Street, a place that looks like a small town.

Our idea was to buy an avocado, remove as many seeds and grow many plants. You will recall that in 1950 the avocado was a product of the most exotic. We were able to find it and buy it and walked triumphantly to the office. A lady in front of us dropped the bag. Colin came out quickly, picked up the bag and handed it gently to the woman. He waited a little ', then said: "Could you tell me thank you." And she gave him a slap in the stomach!

We cut the avocado in the office and we were really bad that he had discovered a single seed. Days were simple and naive.

Well! We celebrate the memory of Colin joyfully recognize our debt to man kind.

Constant influence

John Pilgrim

As are some of our expectations.

The expected time can be unexpected.

When it arrives. Comes when we are absorbed differently from other urgent matters.

These words from Murderess in the cathedral, now have a particular sound. I was writing the obituary of another friend, John Rety, when I heard that Colin Ward was dead. They are both in my mind. Rety was John, who then ran a underground magazine called Intimate Review, asking me to go to Club Malatesta

"Rumor" he said to me conspiratorially, "that there should be anarchists. See what you can discover for us." Having no idea what they were anarchists, we went with some trepidation. There I was so impressed by Philip Samson, who took a copy of Freedom. Then, when Colin launched Anarchy, I subscribed also to the magazine.

At the time I had a bookstall at Charing Cross Road. One day we passed Colin Ward, began to examine the science fiction shelves and asked me to write a piece on the topic for his magazine. Subsequently, a revised version of that article made me earn a scholarship to college for adults. This important turning point in my life had been a direct result of the spontaneous and generous intervention of Colin.

And it did not stop there. At first I was going to study history, but I read articles of Anarchy of those who knew how the group of sociologists of Colin. Jock Young, David Downes, Stan Cohen, Laurie Taylor, who would later become important figures. Then why I chose to study sociology and politics.

Colin has always influenced me. When I asked to speak on the subject of anarchy in a conference in Hull, at the base of my speech I chose his book Anarchy as an organization.

We met again when I moved to Suffolk. Because of time problems had asked me to draw a memory of Ron Fletcher, a former professor of sociology at York and my Commissioner External exams in Hull. "I do not know him well," I said. "I've only seen getting into a car once." "Simply" he said. "And then you know his books." So I had to write again. One can say that has influenced so much direct my life.

The most important thing is that Colin has developed a theory of organization and a desirable social change much more sense than some top-down ideas of official ideologies. It is no exaggeration to say that his ideas on housing, education, unofficial structures of everyday life have influenced the thinking of many people around the world.

It would be particularly appropriate to entrust the Chair of Social Policy at the London School of Economics. He was a self-taught, having left school without graduating, as the founder of that department, and Richard Titmus, as the latter has left its mark thanks to its pure intuition.

I think Colin would agree with another character in Murder in the Cathedral, which says:

I do not see anything definitive in the art of temporal government.

Only violence, duplicity and mismanagement frequently.

They have only one rule: take power and keep it.

It does not come up with something today?

I had some reservations as to whether to sue twice TS Eliot, the wonderful eclecticism but I think Colin would take it the right way. After all, he was able to create much of its sociological thought from a Jewish theologian called Martin Buber.

I'm not sure how he would react to the spectacle of a conservative prime minister in pectore, who sings the praises of workers' control and mutual aid. I suspect that would not have considered a sign that the world was about to be hoped that given by the Central Committee of the Tories. His watchwords were federalism, mutualism, cooperation and community.

Colin said that his ideas come from and Pyotr Kropotkin, Gustav Landauer. The understatement was a typical trait of his character. Its originality lies in the connections he made, applying the ideas of those who had influenced the practical problems of the twentieth and twenty-first century. He could be so incredibly prescient. Forty years ago signaled the approach of the problems of expensive home. And of course, was among the first to grasp the emerging crisis of water.

His genius was in creating connections. He was above all a great imagination in the social field. Wright Mills said: "The fantasy is to understand the history and geography, and relations between both within society." Colin had that kind of fantasy. This has been demonstrated in some thirty books and countless articles and conferences. People took note and then things proceeded differently. He had started (or restarted if you prefer) a tradition of radical rethinking of traditional knowledge.

The world is a better place because we lived like a Colin Ward. It was and remains an example to us all.

|

Colin Ward |

What was it like to have a daddy like Colin Ward

Ben Ward

While I am his only biological son, Colin, in fact, has played an important role in the growth of five children in total. Alan and Doug Balfour in the fifties and sixties, Barney and Tom Unwin in the sixties and seventies and me in the seventies and eighties.

He has contributed in different ways to our well-being, helping Doug in his apprenticeship as a carpenter, drove Alan to research and write about blues music, it is related to Tom through his book Anarchy in Action, and supported me by coming to Barney and listening when we played in pubs.

Colin was a very kind father, who did not interfere. If his sons degenerate, rather than rage, to scold or give them to us, he let happen what must happen as a result of our actions. If we sat in the wrong companies, allowed us to disentangle themselves, without expressing his disapproval, and no way lead us to rebel even more. It is likely that certain characters that we brought home, instead of doing so ashamed of, they did smile.

A good example of the character of Colin accommodating and helpful that this story Barney may have recalled, dating from the mid-seventies.

One afternoon Barney and Tom had gone to throw a few kicks the ball to Wandsworth Park, in south-east London, when on the road, one of the two managed to break a window on the right in front of a house. It turned out the owner who took them bad words, pretending to be told where they lived. The boys told him, then hurried into the park and stayed up late to play, to postpone for as long as possible the terrible moment of returning home and that they should listen to the music.

Gathered all the courage to return, they found the man who had broken the window sitting at the table with Colin and Harriet to drink red wine. Colin had discovered that the guy was manufacturing accordions and if the friend did once, presumably after paying damages without batting an eyelid. Regarding the broken window, not even a word of mouth went out with the boys.

Maybe you wonder if Colin ever participated in our impromptu games of football. He could, only that his body was not a competitive bone. He was not interested in any kind of sport or game, but if forced to take sides with someone, he would always take the side of the most dilapidated, pretending to cheer for football teams like the Stanley or the Hamilton Academical Accriginton, probably because saw these fighters eternal ... or perhaps simply because he liked the names.

His way of teaching us the distinction between right and wrong was led by example and not by preaching. For example, he lived very simply. If someone took the trouble to cook him some food, he always said it was "delicious", sometimes even before tasting it.

When he lived in South Suffolk, if he had to go to London for a day, was walking a mile to the bus stop, took the line to Ipswich and from there the train, instead of asking for a lift to Colchester or me or mother, thus making the journey shorter and cheaper.

If you sometimes wondered how someone would come back from Hadleigh, where was the nearest place to make photocopies, about five miles from home, he replied that he would go on foot, "as God wanted me to go."

He was an avid walker and an enthusiastic user of public transport, eating and drinking he never made the difficult, did not consider himself superior to anyone. Quality is not imposed on us, but we could observe his behavior every day. And then he loved cats so much ...

You would not be surprised to know that we all helped with their homework. Doug received his suggestions for a theme that had to do on Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Alan has inherited his style and methods to accurately make attractive presentations of his project for the River Wandle in 1960. Thirty years later, I was about to go to college, but had not decided whether to study music or philosophy. When I expressed my dilemma, Colin went to the typewriter and returned with this message:

"The world is full of full of musicians and philosophers. But those who prefer to listen to all? "

Left so as to imply that philosophy was an esoteric discipline, accessible only to large brains, the music was really for the benefit of all.

Perhaps the quality that best sums up my memories of Colin and fortunately never lost, even when was giving him everything, was his sense of humor.

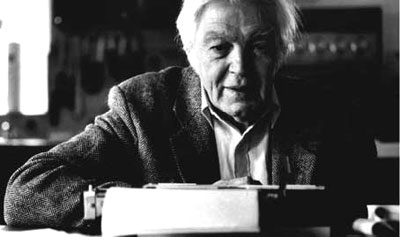

I can still imagine his typewriter or sitting at the table, as he reflects on something with a Craven A cigarette between his fingers, and then I approached and suddenly his expression changed, I smiled and tried to make me laugh. Every time I had a friend of mine, gave him a nickname, like "Big Pipe" or "The Great Moore" and tried to make people laugh too.

Finally, true or acquired as a grandfather, Colin was first of all protective, concerned to keep children away from annoying insects, spiders and rats, and then when the grandchildren were now teenagers and they tended to dominate the conversation, let them do, sat by and smiled in silence.

I think we were just lucky to grow up next to someone so patient and generous, a true man of peace.

Nescafé and a Craven A

David Downes

I met Colin through Sue, my wife, who was then teaching at Woodberry Down, one of the first comprehensive schools from the late fifties until 1961.

Frances was a colleague Sokolov, and it was she who introduced us to John Hewetson (a wonderful man who, as we lived in Bermondsey, became our family doctor for some time), and Colin Philip Sansom. I had never met people like them. Questioned every manifestation of conformism and was immediately clear that Colin had a particularly unusual idea not only how they should be the life and society to be good, but they could be here and now. Animated discussion of art, science, music, ideas of social change, the staid without gloom I used to see in the left. They had a great sense of the ridiculous, but is not mocked of my clumsy attempts at sociological research on crime, but took them seriously. Colin published a few articles and some reviews I wrote about crime, justice and the school of Anarchy, a magazine whose articles were often written by him and signed with a pseudonym inspired by the names of the streets where he had lived. That magazine whose covers were made lively by Rufus Segar for the most part, never failed to capture the imagination and the spirit of the times in which we lived. While I can not claim to be an anarchist, and that done, slowly I came to realize that the meaning of the work of Colin, cultivate and nurture the anarchist ideas of mutual aid and cooperative initiative at the base of each institution, was the best expression of Socialism I knew. He was also a philosophy that you could live in the present, without waiting for some distant revolutionary dawn, invariably false. These were the ideals so eloquently expressed in the books, his first of 1973, the critically acclaimed and translated, Anarchy in Action, to the end and beautiful Anarchism: A Very Short Introduction, 2004.

It was just a pretty lucky to have known Colin relatively early, and was a constant pleasure to continue to attend, with our children, in a meeting that he and Harriet organized at their home in Putney. Among the many good qualities about him that we appreciated were his generosity and his sense of humor. His ideas have always had a certain resonance, especially in Italy, where at the beginning of the nineties was a guest of honor at a conference in Bologna on anarchism. Italian friend who had come to England to do research on feminist post-revolutionary Russia was anxious to know. After chatting with him for some time, had left his mind seething with ideas and with several books that Colin had lent or given away, one of which was the original edition of My disillusionment in Russia, with the signed by Emma Goldman. "I hope you return back," said Colin. "Of course you do," he said. And the book was actually returned, after a few months. Of such aid have been checked by Colin countless visitors and students, not Judith Suissa, the daughter of Stan Cohen, who only a few years ago, wrote a doctoral thesis, now a book on anarchist ideas and education.

The spirit of Colin was memorable. I agonized for about ten years to find the title for a book on gambling. Colin came up so quickly: "How about a fool and his money?" I regret not having used it: he would sell more copies. During his visit to London we stopped to sleep in Wandsworth: we asked him what he liked for breakfast. The answer was: "Nescafe and a Craven A."

A rare praise of Colin came by Stan Cohen, author of classics such as essays Folk Devils and Moral Panics. In the sixties, Colin had published some of its articles of Anarchy. In his room at the London School of Economics, Stan holds a collection of postcard-size photographs of various people, a very select pantheon of figures he admires: Samuel Beckett, Noam Chomsky, Nelson Mandela and, last but not least, George Orwell. One day, while I watched, I asked him who he would like to write the biography, if he had the opportunity. Even though his picture was not among them, he replied: Colin Ward.

commemorative

meeting

|

Conway Hall, London,

Saturday 10 July 2010 |

Welcome and introduction

Ken Worpole

Allow me to begin by welcoming you all who are gathered in large numbers in the Conway Hall this afternoon to commemorate the life and work of Colin Ward, a friend, a colleague (and political awareness) of many of us here.

I met Colin in 1973, when he came to lecture at the Centre for Urban Studies of Islington, where I attended a training course for teachers in London. Unlike many other speakers, who tended to present their knowledge as a result of hard research, anecdotal style affable and Colin seemed to have no beginning of seriousness and substance, yet at the end of his contribution we felt supported and comforted in Our teachers work ... and completely unarmed. The most important thing is that I can still remember, almost forty years later, much of the conference, although some of the topics discussed in his seminal book reappeared, The child and the city, published in 1978, and since then continuously reprinted. The audience was completely won over by the enthusiasm of Colin habits for life on the streets and playgrounds, as with so many life skills and socialization that we learn.

After that I began to attend Colin fairly regularly, often at parties in New Society, New Statesman, then in the last ten years, as host, with my wife, Larraine, home of Colin and Harriet Kersey and later in Debenham. I wish here to pay tribute to Harriet Ward, who has clearly guaranteed the intellectual partnership, love and good housekeeping, thus offering Colin emotional and physical space he needed to write so prolifically about his wide and numerous interests. In fact, the same Harriet is a very talented writer and the book in which she remembers her father, Barry Griffin, A Man of Small Importance offers a lively and insightful portrait of the personal and the political culture of the revolutionary generation of her parents in the early decades of the twentieth century.

For this I feel honored that they have asked me to chair this meeting of memories and tributes, and warmly invite everyone to share the memories of an excellent man and a teacher for many.

|

Colin Ward |

Colin as he was in the sixties

Harriet Ward

The first time I met Colin in 1965 was at Garnett College, Roehampton, where we followed a two year training course for teachers, particularly aimed at students of a certain age who want to teach continuing education courses (and we were both two of a certain age': I was thirty-four and Colin forty). I had two young children (who are here today) whose father had died, it seemed to work best in my situation would be teaching. Colin was there (as I said then) in part because he wanted to change after twelve years devoted to architecture, but also to have more time to write.

The course had already been in operation since the previous September, but for some reason we had not noticed of each other until almost the end of the summer quarter. Colin sat in class towards the back of the classroom and taking notes in silence, never ask questions without being noticed, and never moves to the end of the hour. At that supervised the publication of Anarchy, as I discovered later, and was sometimes busy at home to put together the pieces of the magazine or writing a few articles in a hurry to fill a space when an article promised never came.

The first thing about him that caught my attention was a copy of the New Society under his arm was a new magazine that I just found out myself. So our first conversation about some of the articles in New Society, and I realized immediately that we had a similar view on life and, what surprised me even more, so many things that Colin knew the environment from whence the political left, even on progressive education, when it came time to talk over.

But what really amazed me was this new knowledge of his contribution to a discussion seminar on 'environmental education'. Each of us was asked to explain in turn how to structure a lesson on the environment and we, one after another, gave predictable responses, rather than taken for granted: a walk in the country (or in a park, if we had to teach in a urban situation) showing the flora and fauna, the characteristics of the surrounding nature (note that at the time when he spoke of "environmental education", the campaign could think of and relationship with nature). But when it was his turn, Colin left all open-mouthed with a fascinating presentation that made us blush embarrassed for our inadequacy and lack of imagination.

My lessons will follow the path of a tomato seed, he explained, pointing out that the seed through the human body without being digested. Since its origin in a tomato garden of a pensioner, then as a meal in the family meal, down in the digestive system ... and from there into the sewer system, where it can fall into a river to the sea at every stop ... of travel, of course, there would be investigations and discussions.

From that moment I knew that Colin was a special person and I decided that I should know better. So I tried the lunch interval and presented it to the only other interesting student I met, noting with pleasure that they had found funny. Meanwhile, every conversation with Colin increased my interest in this fascinating man. And not only for his intellect! I admired his spectacular mane of gray hair that fluttered in the wind. Thanks to my eyes I had also noticed an eagle cat hair on his pants, another excellent clue.

But approaching the end of the quarter!

As I was going to cement that friendship before the end of the course and before we return to our busy lives I knew that Colin was living in Fulham and I noticed was that the lessons by public transport, while I went there by car, crossing from West Hampstead London. Fulham was more or less on the road (laughs), so I stepped forward, offering him a ride after school. He was always pleasantly surprised by the apparent coincidence of being on the verge of starting right from the door as he left the school ... He could not know that I was sitting in the parking lot looking through my cards until, with the corner of my eye, did not see it tick, and then turned on the engine. Colin, you will not be surprised to know, was totally oblivious to the wiles of women, indeed of all kinds of cunning.

Once arrived at the door of his home, did not take long for me to invite him to drink a cup of tea and learn about the anarchist friends with whom he shared the apartment, Vernon Richards and Peta Hewetson, and his cats, of course, and the two boys growing together, Alan and Doug Balfour, whose mother had died at about the time that was missing my husband. It was the 'companion' of Colin, as the anarchists used to say, so I discovered that he, like me, was a widower, in a sense.

Our relationship deepened quickly in those afternoons after school at 33 Elerby Street, thanks to the long torment of the woman who cared for the children and I waited patiently passing and take (it was Lily of the irreplaceable, that perhaps some of These points).

In the end it was I who made the first step, when I realized that Colin was in love but was too shy to say it. And I was right! Indeed I was! Yet ... yet this man was absurdly low conviction that I had wrong and that 'I would have noticed' that you have chosen a partner to my height, once I had known better.

Once shyly handed me a book of certificates, documents submitted with his application to the College Garnett, who claimed that it would be an excellent teacher (and here I must explain that the course that we attended was for graduates, which was not a problem for me, but Colin had to be admitted pity, because he had left school at fifteen and had just a couple of night school diplomas. That was the point of that bundle of papers addressed "To whom it may concern").

Colin evidently hoped that those beautiful words could also serve to advise future life partner. The quote:

“It is a pleasure, although it is difficult to do it properly, to write about a man of such talent and such integrity, determination and ability is what Mr. Colin Ward ... There are few people who know how to develop ideas, especially on social and economic issues, in writing, as speakers and as conductors of debates, in a way so cultured and authoritative, but it's also fun and enjoyable. ”

So he expressed Anthony Weaver, Senior Lecturer in the pedagogy of Jesus College, Oxford. Another senior lecturer, Bartlett School of architecture, declared himself "personally indebted to [Colin] who taught me a lot."

But the clincher was that of Gabi Epstein, a partner in the architectural firm and Shepheard Epstein, where Colin had worked for ten years, from 1952 to 1961. To begin with, Gabi filled him rave reviews as "our elder architect ... extremely competent and very experienced" and so forth. I speak of rave reviews, because Colin had never had the title of architect, was in essence a designer, as I always said, even if he went on and dealt with the construction contractors. Gabi Then he remembered that Colin was a question as a teacher and not as an architect, and continued as follows:

“The reason why we can hardly find a replacement for Mr. Ward is that in addition to everything I've said before, he has a great influence in our study in general education. I believe that I had never known before in my life someone who is so competent on many topics ... If I had to try a university with a professor in it, I wish it were that professor Colin Ward.”

Over the years I have heard countless stories of funny that study by Colin, and George West, another colleague of Colin and his friend from a life that had worked there. A few years after the course at Garnett College, Colin had applied for a job at Town and Country Planning Association, and this time the other partner, Peter Shepheard, is expressed in terms equally warm to recommend:

“Honestly I can not imagine someone who is more suited for this work of substance and interesting etc.. etc.. Ward is a man of wide reading and, indeed, in our study are jokes in an attempt to discover a topic that is not informed, but we never succeeded. ”

I'm sure many of you know that will recognize Colin in these words more than forty years ago. Obviously, was admitted to the Garnett College, of course, to TCPA and the place had obviously took my heart, not through the words of other people, but his person (though I still had my work cut out to convince him that I was fine). Colin was not only a great brain, but a person with many qualities at home, as I soon discovered, and a man of the family are natural. It was also, as we know, the kinder person, more generous that could hope to meet, without a shred of personal ambition or vanity, he would have had many reasons to boast. Oh, lucky me!

It was not smooth sailing, though. It took a year to reorganize our two family ménage, settle where they taught in schools, find a place to live. That year I read many articles of Anarchy, we even wrote, and in doing so I discovered that I had been an anarchist all my life without knowing it (which I think applies to others who read the texts of Colin anarchy: it's all so sensible ).

We were married in 1966 and we lived until the end of the decade to 19 Schubert Road, Putney, teaching at various colleges and adding a son to our family, Ben. The pseudonym used by Colin of Anarchy when he was in Fulham, John Ellerby, was replaced by a new one, Frank Schubert, and the table was cleared of our spacious kitchen once a month to assemble the pages of the magazine.

For Colin the sixties were important both professionally as personally, because Anarchy is the breeding ground for anarchist philosopher, I hear about a few moments. For me, that decade was the beginning of a fantastically happy relationship, which ended earlier this year. I consider myself very fortunate to have spent in the company of Colin forty-five years.

|

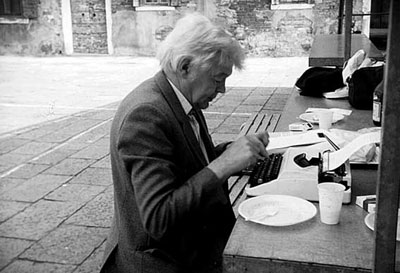

Venice, Incontro Internazionale Anarchico – 1984. Colin Ward |

Colin Ward: how to make anarchism respectable, but not too much

Stuart White

In an article in 1961, based on a speech to a summer school anarchist, Colin asked, "We [the anarchists] are quite respectable?" And he explained: "Not that I care the way we dress, and if our private life is consistent with the statistical norm ... but I think the quality of our anarchist ideas: they are ideas that deserve respect? "

Colin had an acute sensitivity about the reactions of many when they had to do for the first time with anarchist theory: "They look beautiful, but they are certainly impractical." He saw himself as such a reaction would lead to summarily dismiss the anarchist ideas as unworthy of serious attention and want people to exceed the first reaction.

How did he do? With three plausible claims.

The first is pluralism. Companies use various techniques to meet needs and solve problems. They use marketing techniques or the like, which are based on private ownership, competition and the pursuit of individual interest. Employing techniques based on authority, the command, the red tape. Then there is a third technique, or a group of techniques based on mutual help and cooperation.

The 'anarchy' for Colin is nothing but a social space in which the latter predominate techniques of reciprocity. A social space in which we enter (and exit) freely, in which people relate to peers and work cooperatively to solve a problem, fulfill a need, or simply to exercise creativity for the sake of it.

The goal of the anarchist movement is to try to push and urge the society to even greater anarchy in this sense.

Once we understand it in this way, Colin claimed, we see that anarchy far from unrealistic utopia, is already part of our social life. This is the second important statement of Colin: anarchy is not only in the future: it is part of the present. To some extent, solve problems and already satisfied needs, resorting to anarchy. For example, anarchy is already present in the groups of "Twelve Steps", whose members are trying to overcome a common problem with addiction. Its principles are implemented in community centers for the disabled, the mutual aid associations, the Royal National Lifeboat Institute in Wikipedia, in thousands of thousands of social spaces free, egalitarian and cooperative.

It is often present in ways so obvious that we take it for granted. Coming here, I stopped by a newspaper to ask the way, and he has shown me. He did not sell it to me what I got and there are no laws that forced him to give me that information. He gave them free and, in a similar situation, I'd give for free and receive the newspaper, I hope, for free. Here is a need, to some extent, our society meets in an anarchic way, developing a rule of mutual aid, which states how to behave.

Now, if anarchy is already "in action" in our society, if it solves problems and satisfies needs, can he solve more problems and meet more needs.

This brings us to the third statement of Colin, the practicality of anarchy. Colin aimed to show that anarchy is able to meet needs and solve problems where states and markets typically fail or give poor results. For this reason his writings on anarchy never had the form of conceptual analysis, the rule, freedom or anything, but expressed the commitment to real social problems - home, school, transport, energy, power, water.

I think that in this way is able to grasp its purpose and to show that anarchist ideas are 'respectable'.

But I think also that it is important to see that Colin anarchy remains very challenging. It is not easy to assimilate other points of view, the left and the right.

Let's start from the right. The slogan of the new coalition government is "Great Society, not big government." On the one hand, it would seem that is not a slogan Colin could not sign. The underlying message was not exactly what it expected a 'big company' as an alternative to a 'big state'?

Actually, the anarchist vision of Colin does raise some hard questions against the Coalition and its program of 'big company'.

For example, the texts of Colin lead us to ask: to what extent the 'great society' must be applied to economics? It is a corrective to the 'big market' as well as the 'big state'? So, for example, means control of the workers in the industry? It means the substitution of banks to trade with mutual financial institutions? It means relying on production for the community as an alternative to the market?

But the challenge, no doubt, is addressed also to the left. Why, asks Colin, so often that the left wants the State to intervene for the people or on the people instead of making sure that the people acting on their own behalf?

His criticism has exerted great effect on housing. But it also went much further.

For example, many on the left consider the public school a potentially effective instrument of equality. When children 'go wrong' at school (bad compared to the educational criteria), wonder if the school has sufficient resources. Or maybe they fear that the opportunities for children are affected by what happens in the family to have crossed before the door of the school. After that they start thinking about how the state can intervene in families to improve those opportunities.

Colin's approach was very different: a proposed model of school much more flexible, a school with space available for the study at any age, but also with the freedom to learn within the community. He claimed the "modest proposal" not to make compulsory school attendance.

For any supporter of social democracy (which I am) this is an extremely exciting and challenging: it is not easy for a social democrat, while motivated by good intentions, to leave people free to this point, fearing how they might use that freedom . Colin launches challenge to the Social Democrats, constantly asking the question: Why not let them do? Why not trust the responsibility and competence of the people?

In summary, the ideas of Colin continues to raise questions in those who grow conventional ideas of left and the right. For this I think he has hit a target that was really difficult anarchy has made respectable, but not too respectable.

Colin Ward: sower of ideas

Peter Marshall

Colin Ward was a strong sower of the libertarian ideas , one of Britain's most influential anarchists since the end of the Second World War.

I knew him in the early seventies, when he lived in a southern district of London: I showed up in court codpiece in a summer evening in the kitchen and invited me to discuss William Godwin, the father of the anarchist movement in Britain . We had a common interest in the figure of his partner of Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft, but also in issues of allocation and land use, education and creativity of the children's play. Anarchy in Action (1973), his main theoretical text, confirmed my belief in the practical possibility of anarchy, here and now. I appreciated the fact that his criticisms were invariably positive and I was on several occasions a beneficiary. Whenever we were together on the radio to talk about anarchy, I was always impressed by his balanced and insightful comments.

For me it represented the best of the anarchist tradition in our country. Became an anarchist during the Second World War, while serving in the army in Scotland, and since then had remained firm in his belief about the harmful effects of the government and authority and the incalculable benefits of a federal and decentralized social structure of self-managed ies. As he declared in a radio interview in 1968, was "an anarchist communist in the tradition of Kropotkin." He explained very clearly that the anarchist society is "a society that organizes itself without authority" and that anarchy "is a description of a human organization rooted in everyday experience." With these beliefs helped with Vernon Richards, Nicholas Walter and others, to make the revised Freedom and Anarchy, anarchy in the middle of constructive ideas in England. His book Anarchy in Action, based on a series of articles written for the magazines, has seen many translations and reached a circle of readers much wider of only the supporters of anarchy.

In all his writings Colin honors creative potential, the spirit of initiative and autonomy of young people and ordinary people, the oppressed and marginalized by the coercive power and authority. If "freedom for the pike is death for the fish", there is no doubt which side you want to deploy and sustain that freedom. Clearly demonstrated that as a state was tyrannical, as the situation was desperate, you can not stifle the impulses inherent in human beings to create and cooperation.

Having left school at fifteen to work in an architectural firm, and being largely self-taught, Colin would be the first to admit that it has never been a theory in an abstract sense. He considered himself primarily a popularizer and propagandist of anarchist ideas. Nevertheless, with great originality was able to apply his deep sensitivity to his intuition and what he called libertarian "applications" and "solutions" in a broad spectrum of issues, housing, architecture, urban planning, social policy , the assignment of land, the occupation of housing, schools, transport, water. His books, many written in collaboration with other authors, all assume a distinct anarchist point of view and treat all of the relationships between people and the environments in which they live, work and play. In his writings encouraging trends in volunteering, cooperation, democracy in society and hoped the maximum devolution of power of coercion. He always kept in the shade, widely inspired by the works of others and quoting profusely, but his warm humanity always shines through in the pages of his crisp and measured prose.

In his fascinating and with a modest, when asked to write an autobiography, a collection of essays presented his master's favorite, which he called Influences. He had done extensive reading of anarchists and socialists texts, and often acknowledged his debt to Godwin for libertarian ideas on education, to Kropotkin for the concepts of mutual aid and humanization of work in federated networks of autonomous municipalities, to Martin Buber for have highlighted the ongoing conflict between what he called "social principle" and "political principle" to Gustav Landauer for reminding him that the state is not an abstract entity but "a certain relationship between human beings," to Paul Goodman who had clear that a free society is an extension of "spheres of free action" already in place, and finally to Alexander Herzen, who had convinced him of the need to work for change in the present and not for an imaginary future that may not be ever.

Although he admitted the influence of these arguments, had made his much and spreading the seeds all around, even on land that seemed harsh and sterile. Its gradualist and piecemeal approach, focusing on implementation of operating anarchy, has helped to shape and to reflect a generation which he characterized as anarchic "second wave" or "post-left", which is developed in the West since the end of the twentieth century. Thanks to his method of "DIY", underlining the mutual help and self-sufficiency, continue to rise to networks of voluntary associations and cooperatives, and different experiments of libertarian institutions of collective life and community.

Colin will be counted among the great English anarchists of the second half of the twentieth century as one that probably has most influenced social policy and environmental design. It is characteristic of far-sighted and generous man that at the end of his long and productive life, he wrote, the conclusion of his Very Short Introduction to Anarchism, which in the twenty-first century "the best prospects for anarchy will in the ecological movement. "

Colin was a man of great modesty and always preferred to overlook their important contribution to anarchist social theory. Like an old Taoist sage, gave an orientation of the shadows, so that everyone could say: "We did it", without realizing its influence benevolent and smiling.

As long as freedom, justice, kindness and friendliness are considered important values, Colin will remain as a "seed beneath the snow" (to use one of his favorite phrases), ready to germinate wherever there is thawing in the winter of Western culture.

|

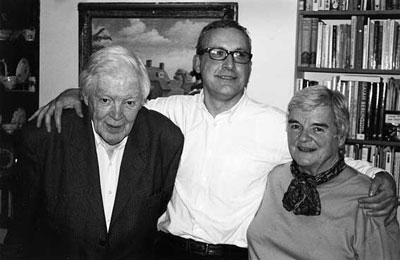

Debenham (Inghilterra) – Francesco Codello in the center

between Colin Ward

and wife Harriet, in their home |

Colin at work

Tony Fyson

In the few minutes to try to give an idea of working with Colin as he was. For eight years, in the seventies, we shared an office there, Colin always manifested the intention to leave his jobs to devote full time to writing.

Both were hired by the Town and Country Planning Association, with previous experience of teaching courses in continuing education, to create a new unit of environmental education. The main purpose was to develop an environmental awareness in secondary school level, but with an emphasis on the built environment and the training of future citizens to participate. I was the deputy to Colin, and along with Rose Tanner and later a teacher of art, Eileen Adams (now present) formed a team of four.

We began work on 1 April 1971, after spending the weekend before moving in helping the association, an advocacy group volunteer professional interests, which left the decrepit site of Covent Garden to settle the impressive Carlton House Terrace, thanks an exceptionally beneficial multi-year lease, signed by the delegates of the Crown (which I still regret it!).

The TCPA offered Colin the happiest years of work, because one of his maxims said that job satisfaction is directly proportional to the degree of autonomy that leaves. The association's director, David Hall, was pleased with the originality of Colin and encouraged in every way.

Thanks to his long experience as editor and contributor of the anarchist weekly Freedom and his creature, the monthly Anarchy, not surprisingly, the first thing he did was to launch a new magazine for teachers, the Bulletin of Environmental Education, known as the BEE. Then came the experience of cutting-edge of Town Trails and Urban Studies Centres, the emerging techniques of civic education, recognizing the importance of technical problem-solving and conflict resolution studies to give life to local teenagers. Colin saw and developed ideas related to active learning and "attendance at school" and later, with Eileen, he developed new methods for visual and tactile education of the urban scene.

Colin was one of those rare people who live and work according to the ideals they support. In this world, people come together to cooperate on tasks and projects with a leadership changed hands according to the interests and capabilities available. No job is too difficult if the final product and the limited resources dictate. So it was for Colin, Rose and me, as for all staff in the TCPA, which we committed ourselves for about three weeks to assemble, staple, stamp pack and the first issue of BEE. Thirteen thousand copies were printed collated internally with a primitive offset printer and then sent to all secondary schools in the country. They were addressed to the responsible of the environmental studies, with the knowledge that at that time there wasn't even a teacher with that position. Colin wanted to point out that environmental issues would have more weight in school curricula. At the peak of successful BEE had twenty-five hundred subscribers, teachers of various disciplines.

Colin had no formal education after the age of fifteen, which is why he felt no awe of a particular academic discipline, and rejected the idea that in the teacher saw a controller, he was convinced that the student was not a vase which pour out or a piece of clay to be molded according to the wishes of society. He preferred the metaphor of the flower to grow. One of his favorite quotes, repeating from memory, a sentence was the architect WR Lethaby, an early supporter of the TCPA, which in 1916 had written: "In the first part of my life I fell asleep telling me that ours was the richest country in the world, then I woke up to discover that wealth meant for me study and beauty, music and art, coffee and omelets. "Colin wanted to present those values to young people and saw an opportunity to do so in the rise of the movement in environmental studies.

In essence, Colin was a writer until fifty years old had been focused in the production of polemical articles and comments often anonymous or signed with a pseudonym. The TCPA began his work as author of books, which would have earned more than thirty titles in three decades, while continuing to write regular columns for magazines and to hold frequent prestigious conferences.

All this prodigious output of writings was achieved without the help of modern technologies. The old typewriter and corrector band have never been supplanted by the computer. He wrote without ever relying on the electronic cutting and pasting in use nowadays. His style was accessible and not far anecdotal and theoretical or academic. He wrote as he spoke, with modesty and erudition. His writings contain many more citations because, as he said, never saw the reason to rewrite the text of someone else to make it look up the ideas of others.

In the office we shared was still chatting happily while I wrote, always with a cigarette between his lips. The normal context of the work involved jokey banter, funny verses of songs for which he had a particular fondness. His musical tastes ranged without limits, so it was not a surprise if the Parlour When Father papered-throated there we followed the hand darem comically interrupted by some oath Cockney dialect. After the article or chapter, took out the last sheet from the typewriter, he clapped his hands on his knees and exclaimed: "Here we are. All good stuff, not crap! "

This was just one of his stock of sayings, many of which, I must admit, I entered in my family lexicon. To respond to some particularly stupid stance of a right-wing politician used to say, with a conventional pricking the left: "When the revolution comes, cut the feet." And his favorite comment in front of certain purchases a little 'expensive was. "No matter the price: we give the cat another canary."

Inevitably, had become a more well-known in national and international level and had to say no to many who asked him for an article or a lecture, or asking him to participate in an initiative. When he passed me, his deputy, an invitation to participate in any international event, said they "do not believe abroad" and for years it was limited to an occasional trip to Holland and Italy, to meet anarchists friends.

When he finally was persuaded to intervene in a training environment in Washington, found that its the same flight was his old friend John Turner, an expert on squatting in the Third World, who invited him to go along with him to some high level meetings of the International Monetary Fund on the occupations of houses, between classes of the course, and there Colin gave some impromptu contributions, but of great impact. Colin, though, the most interesting moments of the trip were his forays in the most squalid quarters of the city, liked them immediately, almost without realizing it and picked up a lot of material from the people he met.

Colin knew how to lead his employees with kindness, showing where he can consistently act in a productive way a person of authority in a hierarchical universe. Inclusive and tolerant of colleagues, authoritative and confident in his writings, shy and with a great sense of the ridiculous, he did not see a reason to put his person first instead of his ideas.

He was a man without a trace of egotism. A great wealth of self-taught knowledge, a huge talent for communicating clearly and convincingly, without arrogance, without competitive pressures and without the will to assert his superiority, all qualities that made him a very special person. Anyone who knew him, personally or through his writings, his memory will be dear and will face life in a different way because of him.

The depth of his insights into the social and political help to illuminate our future. And those of us who were lucky enough to work with him will always remember with affection and gratitude his generosity, his spirit and his friendship.

On the edge

Dennis Hardy

I got to know the writings of Colin in the seventies, when I did my best to interest to urbanism the science students. First there was Anarchy in Action, which threw new light on the subject and then vivid and regular and always interesting copies of the BBE(the bulletin of environmental education co-edited with Tony Fyson, who has just spoken there).

Soon after the rise of Margaret Thatcher (in a sequence of events unrelated to each other, I might add) I managed to get some funding to support a project that would reconstruct the history of an original type of settlement, those who were called the plotlands. My personal interest was aroused during a course on the field with my students, who had led me to Peacehaven on the south coast, a disaster for local officials in planning, but also a place that was worth knowing better.

Advertisement appeared in newspapers that offered a grant for a researcher who worked with me to the project and, to my surprise, I received a request from a certain Colin Ward. It was as if I had tried the players for a football team take the field saw the country and a famous champion. Needless to say, had the bag!

The satirical magazine Private Eye reproduced the ad, which was followed by the Evening Standard that an article fulminating against the waste of public money represented by such research. Since we knew that we had to act well and so began what would be a fascinating journey and hopefully of some use.

Most people had never heard of plotlands as such, although you would recognize them immediately, if you had the name of some places, such as Jaywick Sands and Shoreham Beach. The topic - experience of self-built settlements and mutual help, the man in the street that makes a mockery of authority - was tailor-made for Colin.

A few years before, in fact, Colin had written some articles, and the BBB of New Society, about a brave inhabitant of the East End, a lady that Granger, who in 1932 had had to borrow a pound as an advance on a plot of land in Laindon, Essex. She and her husband, who was a doorman in a popular apartment building, had managed to set up a tent, World War I war surplus , on that ground, and the two were devoting weekends to building a whole house for them. Then, finally moved there, we reared chickens, geese and goats, and cultivated a vegetable garden. The important fact is that, thanks to their efforts, although poor, were able to make a owned home.

The story of Mrs. Granger was repeated in all the places we went and spent many sunny days moving from side to side along the coast and the countryside south of London. At that time Colin was living in Putney, so we met in the morning at a station in London and then off to some other "eyesore in the landscape."

In addition to other poor families who had made it, we met a group of people a little 'bohemian, who were attracted by the prospect of spending the weekends and the holidays near the sea in a railway carriage or in an old converted coach. We discovered that the beach was a place of Shoreham frequented by celebrities of the London theater scene, running to Victoria Station when the curtain fell, to catch the last train that would take them to shelters in their own sea, with evocative names like 'Cinderella' or 'Sleeping Beauty'. For the locals was the fact that some take their holidays and at weekends were more than raise an eyebrow.

Colin was at ease with both the actors and with the workers and the conversations were never a problem as we were sitting in some cozy retreat with paraffin lamps and chintz curtains and listen to various stories. Understandably, those places attracted artists and we happened to get to the hermitages of the sculptor Jacob Epstein likes of painter Mark Gertler and, like that of the writer and director Derek Jarman at Dungeness beach.

In addition to colorful portraits that we gathered, there was obviously a more serious side and we tried to show how the experiences of the inhabitants of plotlands could be useful to address our housing problems. We were in the eighties and the idea of DIY was not a thousand miles away from laissez faire of Thatcherism. Colin was a great admirer of the work of architect Walter Segal and claimed his experiment of self-construction of Lewisham. By the same token he was a fervent supporter of the TCPA and wrote a beautiful article on the subject, titled "A DIY New Town" - "a new city do it yourself".

Looking back, if you need to remember, you can see that Colin was an original thinker, able to observe from a different point of view deeply rooted and unresolved problems. He always had on hand the right of the library anarchist literary source and a memory drug. In addition he was a great friend, kind, funny, smiling, and together we had so much fun in the situation that you would classify "work" with Colin but were always pleasant.

At the time the research was completed plotlands (and published under the title Arcadia for All and reprinted several times by Five Leaves), there was still some work to do. In our laps in the most marginal of the coast we were intrigued to discover in a zone close to another strange plotlands English institution, the holiday camp. So one thing followed another and continued to work together to write a history of British holiday camps.

Some of you might wonder why a good anarchist Colin deals with a matter that is almost synonymous with regimentation. I think the answer lies in the parallel stories of so many poor people were a holiday for the first time, a spirit of camaraderie and community that characterized even this form of collective resort in the mid-twentieth century architecture that goes hand in hand with the seaside resorts.

Our book on the subject, Goodnight Campers!, Has been sold out for some time and Colin was anxious to see it on the shelves of libraries. Thanks to the efforts of Ross Bradshaw, Five Leaves and issues, today released a new edition. Colin would undoubtedly have been happy to celebrate the release.

An instinctive distrust of top-down solutions

Sir Peter Hall

Collaboration with Colin Ward's book Sociable Cities: The Legacy of Ebenezer Howard, which we published in 1998, was a unique experience. One could cite Orwell out of turn and say that all experiences are particular co-authorship, but some are more special than others. A definition that could give you is that Colin was a rather inconstant collaborator. I sent him the first draft of a chapter and he made some small comment, which I always kept the account. He sent me a chapter and I did some minimal commentary, the same way, once inserted. But here was the problem which others have alluded to: Colin was resolutely averse to abandon the communication technology that dated back to 1873, represented by the brand Underwood portable typewriter, which now occupies the place it deserves in the context of memories.

In 1998 we were in the midst of the digital revolution and this meant that it was my duty to add his text in the scanner in my house. But the long use of the machine had produced the effect that every time you struck the key of the letter "g", the character ended up moved higher, with the result that the scanner read it as if it were a "9".

The solution was obviously in an overall "search and replace", which was fine, except that the year 1998 became 1gg8. Together with Ann Rudkin, effectively revising the text for the editor, sometimes we had to bring the text to the end of the twentieth century. Colin, of course, remained blissfully unaware of everything.

There was another more serious issue: Colin happily passed my last chapter, calling for a broad new plan to create large knots of settlement along the lines of transportation in the south-east of England, found that five years after a 'echoed the government's strategy of developing sustainable communities. This did not seem right to Colin, if not for the fact that this solution could provide a context for all types of local initiatives. And the central idea of our book, we shared with passion, was to raise a question: how we should interpret the philosophy of Ebenezer Howard, whose famous pamphlet, To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform was published exactly a century before, in 1898? Howard's garden cities were a result of anarchist thought that had a great influence at the time and had produced a year after the equally influential book of Kropotkin, Fields, factories and workshops. The garden city had to be made thanks to the cooperative of small groups of ordinary people, with the help of commercial mortgages granted by wealthy individuals. The words at the base of the famous diagram of the three magnets Howard, Liberty - Cooperation, were not mere rhetoric but represented the core of his ideas. In this essential sense, much of what Colin had written on urban issues reflected this line of thought important but forgotten urban English.

I want to pick a thought already expressed in the presentation of Ken Worpole: Colin's writings for the magazine New Society, a quarter of a century from 1962 until his sad loss of independence in 1988, played such an important role in the spread of new ideas in social sciences. After a brief start-up period in which it was directed by Tom Raison, who left to become a Tory Parliament, passed into the hands of Paul Barker, an extraordinary journalist who has just celebrated their golden wedding anniversary. Paul was and is basically an iconoclast who welcomed the original thinkers in its pages any orientation - Reyer Banham, Colin MacInnes, John Berger, Dennis Potter - whose essential feature was to criticize the induced knowledge. In 1969 he invited three of us - Reyer Banham, Cedric Price and me - to work for a special issue, Nonplan. An Experiment in Freedom. It provoked a storm and the subsequent resignation of the Deputy Director, Brian Lapping, who then made an independent career as a television producer. Even today, the poster is the subject of conferences and debates.

Do not know why Colin has not participated. Perhaps, like Groucho Marx refused to join automatically a club that wanted him as a partner. But this episode highlights an important fact: Paul Colin shared with an instinctive distrust of top-down solutions and was convinced that the individual has limitless creativity. One of the tragedies linked to the disappearance of Colin is that we can not read his review of the new book by Paul, The Freedom of Suburbia. That would no doubt have appreciated. [When I made this comment to the memorial meeting, I did not know one more thing: Harriet whispered: "He was reading it when he died. It is still next to his chair. "] This, surely, is a reminder not up to Colin.

Colin Ward remembered

Eileen Adams

II wear these clothes, which are the ones that I wear when I go on vacation, this jacket, the closest thing that I have a Saharan Africa, in memory of Colin. When holding a conference, the first question was about the topic of course was talking about, and the last was: Where did you get the Saharan? (She had made for him Harriet) An icon of fashion is not exactly the first thing that comes to mind when you think about Colin.

The first and most lasting impression was when Colin was generous with their ideas, his time and attention. Sometimes, as children made us miss a day of school for some important public occasion. As a young teacher, I was given a half day of freedom to meet Colin Ward, it was confusing because I too have to teach and talk to him at the same time. To prepare for the meeting, took from the library all his books I could find. He came to my apartment and promptly emptied his bag inflates to give me his books as gifts. Since the first approach he has been kind and generous with me, as it was with everyone. But when he realized that I already had many of his books, he put his copies in the folder. I was too shy to tell him that they did not belong to me. I could not imagine that a few years later he signed with me on my first book!

He worked in what was the coal shed of his house in Suffolk. The table was an old door balanced on two stacks of books. I was sitting on a garden chair, next to boxes of apples. Colin wrote with small portable machine that had given to me for my fourteen years, because his was broken. I will never forget the happy tick-tock of the keys, the buzzing of bees and flies, the air perfumed cross my mind, drowsiness enveloped me in the evening, when Harriet called us at the table for dinner. Our book was about how you develop your sense of place that feeds the intelligence of emotions.

Colin walked me toward a particular career path, which combines art, design and environmental education, starting from the Royal College of Art and the Front Door project at Pimlico School in London (1974-76), then working with him to the project Art and the Built Enviromnent the School Council to the TCPA (1976-79). The projects were developed during a period in which the pedagogical thinking was permeated by the ideas that put the child at the center, and those of social justice and participatory democracy. Colin called our work a lever for change of school and a mean to empower children.

Collaboration with Colin influenced my world of understanding the world, to think and work. Which I am very grateful. As a fellow, I have always had great respect, admiration and affection for him. It's not often that one can speak well of his boss (I use that word deliberately). He was always so fun it made me laugh! And, more importantly, made me think! There were many opportunities for indirect learning: I accidentally stuck my nose in a book, an author quoted, made an observation tank, put me in an unusual situation, I threw a challenge. I knew he would come to help, he would have saved me if I had got into trouble. As a friend, always had a positive attitude, encouraged and supported, even though he said that getting older is rising optimist in the morning but going to sleep pessimistic.

In my role as an educator, a supporter of youth participation in the transformation of the environment I was inspired by his ideas. I do not do everything alone. Colin has influenced a generation of educators around the world, saying that education to the urban environment was an exciting field of study, an important and challenging. I was fortunate to meet many of these educators. It was Colin who directed me towards international collaboration. One day there came a letter from the International Society for Art, which invited him to Paris for a weekend of seminars.

"Paris," said "is in France, isn't it?"

"Yes," I answered.

"It's foreign, isn't it?"

"Yeah," he assented.

"It's your department."

The decision, rejected the objections, I went to Paris for the workshop, followed by a conference at the Centre Pompidou from another trip as a consultant for a television producer, all because Colin had decided not to travel!

For forty years I have had the great fortune to work in twenty-three countries and have been able to share Colin ideas with many others. I've never managed to even approach his skill as a lecturer and I would have been impossible to fit into my attempts to its original style. But I remember it as if he was sitting with air and then crumpled rose springing up as if to come to life when it was his turn to speak. I remember how lively and convincing when he told exposing his arguments, he knew how to entertain with stories and anecdotes and humorous tone to his words. Questions answered frankly. Nobody went away from his lecture without having in mind new views and new ideas. I tried to emulate his method of teaching in my lectures across the landscape, the interdisciplinary collaboration in the school, education for sustainability, public art and the Power Drawing. On all these occasions there have been similar efforts of conscience, to act, to develop the ability to participate in cultural life and to shape the environment.

Colin is famous for his work as an anarchist, but I see it more as a humanist. Humanism is based on the characteristics and behaviors that are considered the best in humans. Colin believed in the best of people and was able to pull it all out.

|

Colin Ward |

Colin Ward and the revolution in human relations

Roman Krznaric

The day I learned of the death of Colin, I collected his books in my library - at least twenty titles on an amazing number of topics - and stayed up all night to read. Influences is one of my favorites, which speaks of the thinkers who have shaped his worldview, including Alexander Herzen, Mary Wollstonecraft and Paul Goodman. That night I realized how I had been influenced by Colin, and offered new ideas and inspiration for my approach to the art of living.

I met his lyrics the first time in 1997, the anarchist paper Freedom, I started reading as an antidote against the press officer who was obsessed with the general elections that were held in that year. Then soon became dependent on his book, Anarchy in Action from classic to quirky titles such as Goodnight Campers! The History of the British Holiday Camp. Later I became a friend of Colin and his wife Harriet (herself a formidable thinker and writer) and for a decade I have regular trips to stay with them in Suffolk. Colin was a nice person and a wonderful talker. She had a girlish laugh, a flash of malice in her eyes, and every so often or put to sing out loud while chewing a sausage, fishing from his extraordinary memory - which unfortunately has been fading in recent years - in the words of the songs his childhood in Essex in the thirties. Not surprisingly, his son and his two godchildren have ended up being musicians.

Despite having achieved an international reputation and are often invited to speak all over the world, rarely took advantage of the opportunity to travel abroad. Instead, for him one of the moments of glory during the week was a bus trip (did not know how to drive) from his home in the countryside to the city of Ipswich, where he was going to the movies with Harriet and made forays into the local library, of which he must have been the most ardent users. Back home, when he did not read much of the time spent to beat the keys of his typewriter, to pull out another book by Colin Ward or to respond diligently to his correspondents - anarchists Korean, Norwegian experts in development concessions, and many its other international partners.

I admired in him above all the ability to see the good in people. Not wasting energy to pick on those with whom we did not get along and usually managed to find a kind word for them. American anarchist Murray Bookchin, the notoriously edgy character, once said: "I'm glad to see you up every two years, so we exchange information on health and family without talking about what we can unite or divide." This was the most critical of which could go and was very careful to avoid internal squabbles in the anarchist movement. I think we could all learn from him, who understood that the purpose is to contribute ideas to create the world, not destroy it.

The story about him that I prefer (and I may have unconsciously embellished over the years) refers to the time spent teaching the subject then in vogue of liberal studies at the Wandsworth Technical College in London in the sixties. Many of his students were apprentices in the construction industry and when he came to hold the first lesson he asked them what they wanted to learn - what difficulties encountered in life that he could really help you to overcome. It turned out that their main concern was the lack of sleep. Then Colin's head was filled diligently scientific knowledge on sleep and went for a semester to lecture on the art of sleep. It is a story I was always impressed as a teacher, the ultimate example of how we can commit ourselves to meet the needs of students.

For most people the image of the typical nineteenth-century Russian anarchist is a bomb or a young man with the black hood of today's anti-capitalist demonstrations. Colin did not correspond to any of the two images. He came from a different anarchist tradition, one that saw the emergence of social change not by violence and revolution, but the expansion of cooperation and mutual aid in everyday life. His writings extolling the worker co-operatives, associations of tenants, assignees of plots, play areas for children, mutual aid societies and organizations such as the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. It was there that he saw "anarchy in action" - people who are organizing on their own, voluntary, non-hierarchical and decentralized - a social model that reflects the anarchist theory of the personality that had the most influence, the writer Russian geographer and Kropotkin. Colin was convinced that an anarchist society is not envisaged a situation in a fictional future, but one thing that existed here and now, all around us, a latent force, "like a seed beneath the snow," as he was wont to say, who has the ability to roll back the boundaries of the central state and the capitalist system.

Colin liked to quote Gustav Landauer, German anarchist of the early twentieth century, who wrote:

"The state is not something that can be destroyed by a revolution, but a condition, a certain relationship between human beings, a way of behaving; it can be put down by establishing different relationships, by behaving them in a different way."

Hence the idea that social change comes not from new laws, new governments or new policies, but by a revolution in human relations from the bottom up, changing the way individuals treat one another. It was a method that has deeply affected my way of thinking, away from my previous interest in the traditional parties and state power (I was a researcher in political science at the university) and pushing me to develop my ideas on empathy as a force of social change. Colin what he writes on social thought of Martin Buber, in his book Influences introduced me to another thinker who has influenced my beliefs about the strength of empathy.

Outside the anarchist circles, Colin has had a major influence as a scholar of social history and oral history, showing its readers to hear voices and making unexpected landscapes generally ignored by traditional historians. His book, The Allotment: Its Landscape and Culture (written with David Crouch) has the qualities of brilliant improvisation of horticulturists, and The Child and the City has revealed the extraordinary creativity of children playing in the streets of the suburbs. One of his last books, Cotters and Squatters, a history of occupation of houses and land in England from the seventeenth century, is characteristic of his work, which brings to life an entire Social subculture known only to few. One of the qualities that make his books so fascinating, beyond the extraordinary range and originality of the arguments, is its dialogic style, its accessible prose, it is quite allergic to the theoretical and academic jargon. For this reason I consider him one of the great political communicators of the last century, along with authors like George Orwell. As I write, I have before me a picture of Colin staring at me, which keeps an eye on not only the quality of my ideas, but also my way of expressing them.

Colin felt an extreme aversion to nationalist separatism, religious or political. Rejected the simplistic ideology and patriotism that brings people to kill each other. In 1942, in the darkest days of World War II, the sixteen year old Colin decided to copy these words written by journalist Bill O'Connor in the Daily Mirror:

“Our children are protected from diphtheria by what they have done a Japanese and a German. Do not take smallpox by the work of an Englishman. They avoid the rage thanks to a Frenchman. From birth to death are surrounded by an invisible band: they are the spirits of men who have served with nothing but absolute loyalty to the welfare of mankind. ”

Colin loved this quote, considering the center of his world view, and gradually came to be the star of the same words. Colin Ward is now part of that invisible host which surrounds our lives, whose work continues to quietly shape our health and create the revolution in human relations which we desperately need.

| Reading Colin Ward (in Italian) |

Anarchia come organizzazione, Eleuthera, Milano, varie edizioni.

(a cura di Colin Ward), P. Kropotkin, Campi, fabbriche, officine, Antistato, Milano, 1975.

Dopo l’automobile, Eleuthera, Milano, 1992.

La città dei ricchi e la città dei poveri, e/o, Roma, 1998.

Il bambino e la città, Ancora del Mediterraneo, Napoli, 2000.

Acqua e comunità, Eleuthera, Milano, 2003.

Conversazioni con Colin Ward, Eleuthera, Milano, 2003.

L’anarchia. Un approccio essenziale, Eleuthera, Milano, 2008.

Per una efficace introduzione al suo pensiero consiglio di leggere di Stuart White, L’anarchismo pragmatico di Colin Ward, Bollettino dell’Archivio Pinelli, n. 30, Milano. |

|